[Excerpt from Dodge City and Ford County, Kansas 1870-1920 Pioneer Histories and Stories. Copyright Ford County Historical Society, Inc. All Rights reserved.]

Looking back at the very early history of Dodge City, it is easy to see that the coming of the railroad was one of the most important reasons for Dodge City being built in 1872, five miles west of Fort Dodge. Those who were stationed at the fort, or were civilian workers there, knew that the fort’s facilities could not take care of the needs of the large group of workmen who would soon be arriving. The rails that were being laid for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad would be laid as far as Fort Dodge, by late summer.

When the A.T. & S.F. tracks reached five miles west of Fort Dodge, in September 1872, enterprising businessmen had Dodge City on the map, waiting for the laborers with food, liquor and lodging. The presence of the rails in Dodge City caused the Texas cattlemen to drive their herds to Dodge City, instead of Abilene, to be shipped to eastern markets, and the settlers to come from the east by train to build homes. During the coming years, as the town grew, emigrants continued to settle in the own or on homesteads and the railroad was built farther west. This progress caused Dodge City to become an important division point with a new freight depot and roundhouse.

By the early 1900s, local labor did not meet the demand of the continuing growth of railroad operations in Dodge City. The A.T. & S.F., like other railroads, found a source from which to draw help and willing laborers south of the border in Mexico.

Descendants of some of the first of these Mexican railroad laborers, the Esquibel and Sanchez families, date their fathers and grandfathers coming as early as 1903. The people were promised homes as well as employment. Although the homes were little more than shacks, they housed these first emigrants for several years. As the demand for more space for railroad tracks, yards and buildings increased, the little Mexican village had to be moved farther east. We are told, that at the first site, there were no more than 10 houses, one of which was sod. When more laborers came during those years, they pitched tents or built crude shacks along the tracks.

At the new site east of the roundhouse, the company built three sections of row houses. Some had wooden planks for floors and a few had dirt floors. Row houses were homes that we would call apartments today. They were built in rows with a passageway between each two houses. Manuel Gonzales, who was born in the village in 1920, explained that one of the rows was built of bridge timbers, not railroad ties. These timbers were longer and more suitable for building. The other rows, and many of the houses constructed around the edge of the village, were built out of scrap lumber. Gonzales could remember the names of all of the families who lived in the #1 row of houses in 1930. On the west end was the Ontiberos family, then the Moreno, Alvarez, Remigio, Navarro, Lopez and Garcia families as one traveled east down the little dirt street. Punctured tires were common when automobiles were driven down these dirt streets as all of the families dumped the ashes from their wood-burning stoves into the streets. The ashes made the street less muddy but there were always nails in the scrap lumber that families burned and those nails were in the ashes in the streets. As the village grew, homes were built individually on all sides of the row houses. They had their own private yards where vegetables and flowers grew on every inch of space, except for the path to the outhouse in the back yard. None of the homes had running water or indoor toilets. There were two hydrants in the village from which water was carried for washing and cooking.

A teacher in the village recalls the sparsely furnished rooms of the homes. There was always a wood-burning stove, a small table, on and above which were religious objects and pictures, a few chairs and usually a trunk or chest. There were beds, of course, but the trunk, the stove and the religious emblems are remembered best. Religion was a very important part of the lives of these Mexican families.

The trunk held the artistry of the mother of the home. Almost without exception the trunk held beautiful crocheted doilies, baby jackets, shawls and even window curtains. These lovely pieces were always starched and ironed. The square glass in the front door was sure to display a beautiful piece of the lady’s handiwork.

The village was not just a group of homes, but a self-sustaining small town. There was a grocery store, a dance hall, a school and, of course, the church. Isolated as they were from the other inhabitants of Dodge City, they became a closely knit community. They shared a common background of religion, nationality and language. The majority of the men worked for the railroad.

Mexican people are by nature lighthearted, happy people, and in spite of poverty and primitive living conditions, their national holidays, birthdays, weddings and births were occasions that were celebrated with much merriment and music. “Las Mananitas” sung outside the bedroom window is about the sweetest music an awakening heart can imagine. A christening with its following feast and fun was very special, but the all-day wedding celebration outshone either of those.

A wedding celebration would begin with the wedding breakfast and all of the friends gathering at the home of the bride for pan dulce (sweet rolls), and cinnamon-flavored hot chocolate, after which the guests went home to dress. It seemed that everyone had a special dress or suit for such occasions. The church was small, but somehow they all crowded in. After the ceremony, the wedding dinner followed. Then all of the guests went home to rest for the really big event – the wedding dance – that lasted until the wee hours.

The two special national holidays that called for fiestas, speeches, pageants, games and dancing were the Mexican independence days of September 15 and 16, celebrating their victory over Spain, and May 5, Cinco de Mayo, when Mexico won its independence from France. Flags, bunting and patriotic posters, beautiful girls representing Mexico and Spain, men waxing eloquent with long patriotic speeches were all a part of those celebrations.

In the beginning years of the Mexican Village, the devout Catholic people were seldom able to get Spanish-speaking priests to preside over services that they could attend. The Carranza rebellion in Mexico, in 1914, brought an end to this problem. The rebellion which led to persecution of the Catholic Church caused many native priests and nuns to be murdered and the foreign-born, such as Spanish and Portuguese, were expelled from the country. Dodge City and other towns with Hispanic settlements profited by this expulsion. The priests and nuns who came here not only ministered to the Mexican population, they taught Spanish at St. Mary of the Plains Academy and helped with the village school.

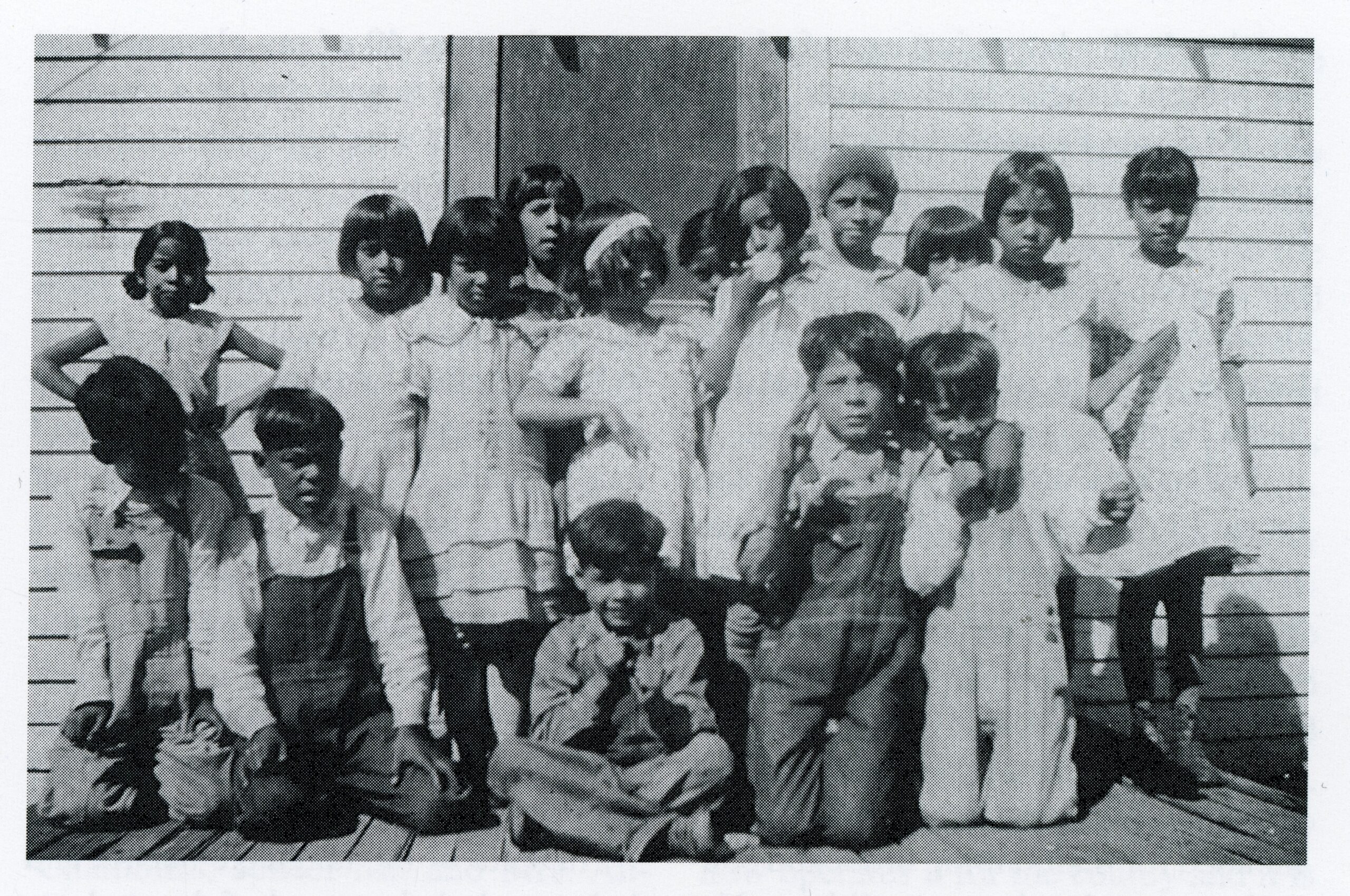

Father John Mark Handley, a Paulist priest, came to Dodge City in 1914, the same year the priests were expelled from Mexico. Father Handley was to become one of the town’s most influential and popular priests. It was he who first realized that the children of the Mexican Village were getting no formal education. Through his appeals, enough money was collected to build a frame school building in the village. He asked Mrs. Faye Burns, who spoke no Spanish, to teach the school. There were 49 students in that first class. Father Arturo Vallve, one of the first Claretian priests from Mexico to arrive in Dodge City, taught religion and read stories to the children in Spanish.

By 1921, Father Handley’s parochial school was replaced by a two-room public school. His school building became the village church. In 1926, another room was added to the public school. In the two rooms only the first four grades were taught, but with three rooms all six elementary grades could be taught. In 1929, the Mexican school was officially named the “Coronado School” by a vote of the students.

Through the years, from 1921 to 1948, many dedicated teachers worked in the classrooms of the little three-room Coronado School. Much of the success of the students there can be traced to the hard work of those educators. Among those who taught at Coronado School were: Delia Joerling, Ruth Parkhurst, Ruth Weber, Laura Fisher, Gladys Crane, Alice Berkshire, Mabel McKinnon, Phyllis Barker, Voncile Gallemore, Hazel Whited, Lola Adams, Vivian Smith and Arthur E. Scroggins. Arthur E. Scroggins served as principal for many years. His interest in the Mexican students was genuine and sincere. His interest in their progress did not end with grade school. He was always there for them with advice or a helping hand in later years.

In the years that followed, railroading saw many changes and improvements. The old steam engines gave way to diesels. During World War II the railroad put a large fuel tank in the middle of the village, destroying the row houses. This forced many families out of the village to homes in Dodge City. On October 18, 1948, the Mayrath Machine Company bought the school building for $1,545. They used it for offices for their machinery company for many years. As the Mayrath Company continued to expand, more of the Mexicans were forced from the homes they had rented for so long. By the 1950s, all had moved away and the village was no more. The school building, the only village building still standing in 1995, is surrounded by machinery instead of children.

Lola Adams Crum

[Permission was given by Tim Wenzl to use material from his A History of Our Lady of Guadalupe Parish.]

Dodge City and Ford County, Kansas 1870-1920 Pioneer Histories and Stories is available for purchase from the Ford County Historical Society.