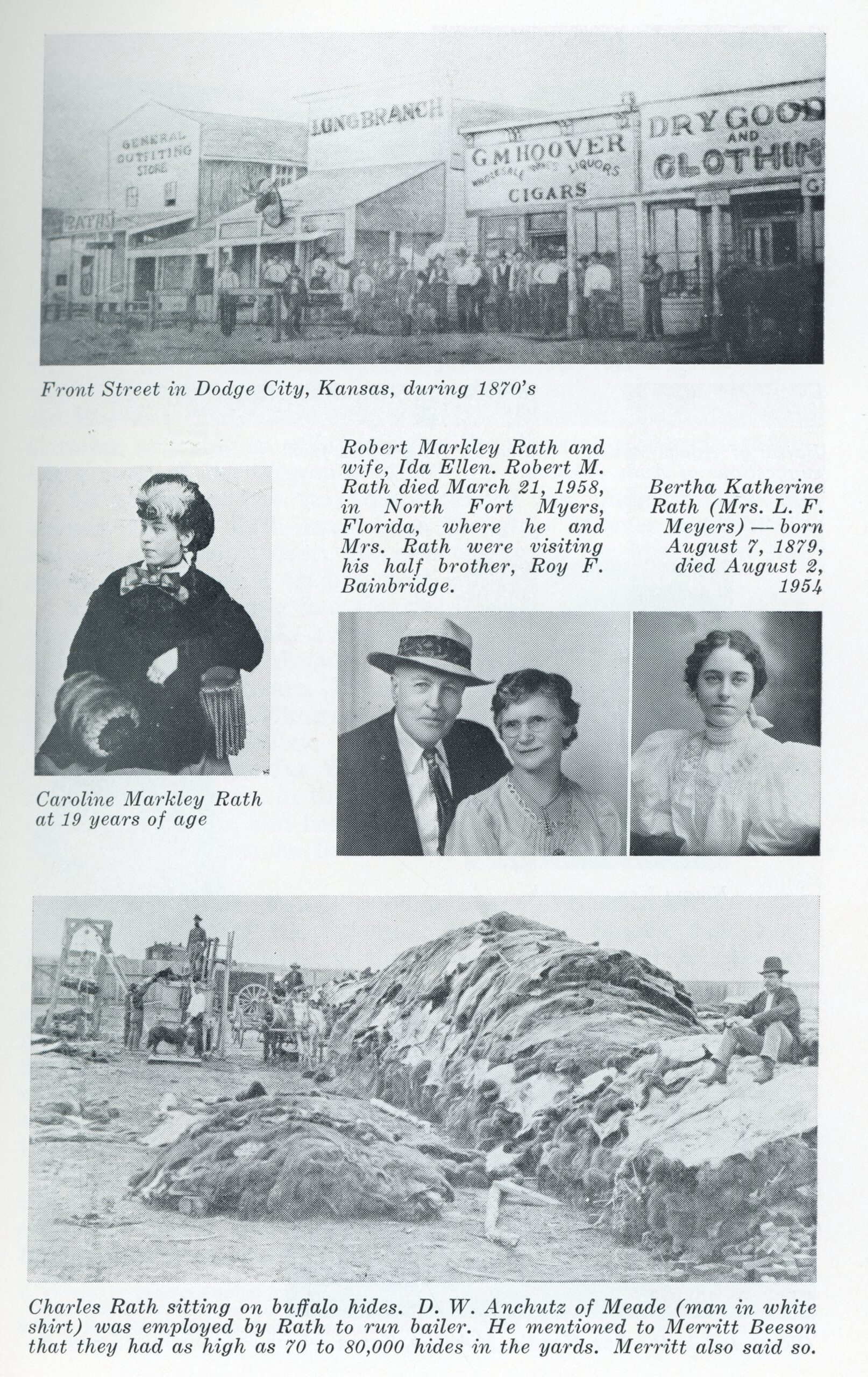

On a day while looking at photographs in Beeson Museum in Dodge City, Kansas, Merritt Beeson, the owner, pointed to a man sitting on a rick of forty thousand buffalo hides. He said, “There is a man who has never had his just due in Kansas – Charles Rath.” Then he brought another photograph. He spoke of this man’s undertakings, his great accomplishment. Although an inexperienced writer at the time, I was greatly moved, the idea for a book was born.

I started the story at once, only to learn how little I really knew about this great man. I began collecting material in earnest. I visited sites in Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, California, and Colorado, spending much time at Adobe Walls, Old Mobeetie, Old Fort Griffin, Rath City, Camp Supply, and along the Rath Trail. I talked with relatives and old timers all along the way during a two months’ trip.

Family history, one gets from day to day, bit by bit, which pieced together, forms a rich background for everything that happens and provides a logical reason for what characters do. With relatives, in-laws, and old-timers, you can ask questions freely and mostly get honest answers, while the little anecdotes they tell are all added spice for your book. But family history in a factual book is the most controversial material a writer gathers. While it adds the personal touch that no other information offers and which no other writer possesses, it is sometimes dynamite to use. Historians will call you, saying there is no record of it. Family history may be right and it may be wrong. However, when the same information comes from different sources, a writer naturally assumes it is correct.

Charles Rath gave up the comforts of home to rove in the adventurous, glamorous West, to become so much a part of the highly courageous men of that day who were always ahead of others that he became a legendary figure in Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas. He became a fairy prince to kith and kin to whom he dealt out money and lands with a lavish hand, an angel of mercy to friends to whom he was loyal and true; an anchor in the time of storms to the many men he employed and those who depended on his freighting trains, trading posts, and hide yards as an outlet for their furs and buffalo hides.

v

To men yet living who remembered Charles Rath, my queries elicited only one answer, he was a man who made things move but was seldom there to see them moving – a nice fellow. He was gentle and kind to his help and always far too lenient in the face of their short-comings. In fact, Charles Rath did little if any of the actual work at any of his many enterprises. He might be in and out of his store for several days at a time but the actual labor of running them he left to those in charge, so much so that shortly the business was known by the manager’s name, coupled with Rath’s. For that reason he became a legendary figure, the strong man behind his enterprises but always away from them.

And it was the same at any of the homes he set up, so much so, that his own children knew little about him. He was at home for a few hours or days, then gone for months on end. But when he drew his driving team or horse up with a flourish before the door, the youngsters ran from the house with their hands extended. Sure enough the long-gone papa would clap a dollar into each outstretched palm. The children ran to the company store and Charles Rath would enter the door of his home. So when he began to stay at home and in his store at old Mobeetie, Texas, it didn’t take much guessing to know his money and lands were gone, as well as the new frontiers where his ingenuity could have laid the foundation for another fortune.

During the 1850’s he worked with men well known on the plains, William and George Bent, Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, Jesse Crane and his brother George; Minimic, Cheyenne medicine man, who scouted for him on trading expeditions; Comanche Quanah Parker and Comanche Chief Little Bear, and the powerful Sioux chief, Spotted-Tail, all of whom were close friends.

No record has shown that Charles Rath ever took advantage of the Indians but does prove that he was a link between white men and the Indian race. He was one of the few men like Bridger and Carson and Bent who could outguess the Indian in any situation that arose and acted accordingly. He respected the Indians but he never trusted them. Although he suffered much at their hands, he was never one to start the military forces after them. But in the case of treaties between the government and the Indians, he rode the plains alone to persuade the Indians to come to the designated place. Thus Charles Rath became known to white men and Indians alike as the bravest man on the plains, his ability never doubted throughout his long, unbelievably prosperous years as an Indian trader, merchant, buffalo hunter, trail blazer, and town organizer.

If perfect people did exist, I should not care to meet them nor portray them for your scrutiny. But I present for your approval, Charles Rath, frontiersman, Indian trader, wagon train

vi

owner, trading post merchant, buffalo hunter and shipper, Indian interpreter and friend, reporter of conditions on the plains and confidant of government men, government contractor supplying wood, grain, hay and food for forts, and contractor for Santa Fe grade work, having his faults and failings as well as his admirable qualities, as one of the West’s greatest men-Not one of the storied men of fame and fable but a great man who did more than his share in the face of danger to make the West what it is today and then stepped quietly out of the picture when that work was done.

vii

viii