AS has been stated, the site of Fort Dodge was an old camping ground for trains going to New Mexico.

The government was obliged to erect a fort here, but even then the Indians struggled for the mastery, and made many attacks, not only on passing trains, but on the troops themselves. I witnessed the running off of over one hundred horses, those of Captain William Thompson’s troop of the Seventh United States Cavalry. The savages killed the guard and then defied the garrison, as they knew the soldiers had no horses on which to follow them.

Several times have I seen them run right into the fort, cut off and gather up what loose stock there was around, and kill and dismount and deliberately scalp one or more victims, whom they had caught outside the garrison, before the soldiers could mount and follow.

Early one very foggy morning they made a descent on a large body of troops, mostly infantry, with a big lot of transportation. At this time the government was preparing for a campaign against them. It was a bold . thing to do, but they made a brave dash right into and among the big mule trains. It was so dark and foggy that nothing was seen~f them until they were in the camp, and they made a reign of bedlam for a short time.

They succeed in cutting about fifty mules loose from the wagons and getting away with them, and killing, scalping, and mutilating an old hunter named Ralph, just as he was in the act of killing a coyote he had caught in a steel trap, not three hundreds yards from the mule camp. Of course they shot him with arrows, and then speared him, so that no report should be heard from the camp.

“Boots and saddles” was soon sounded, and away went two companies of cavalry, some scouts following or at

-100-

least acting as flankers, I among the latter. The cavalry kept to the road while we took to the hills. In the course of time we came up to the Indians-the fog still very heavy-and were right in among them before we knew it. Then came the chase. First we ran them, and then they turned and chased us. They outnumbered us ten to one. More than once did we draw them down within a mile or two of the cavalry, when we would send one of our number back and plead with the captain to help us; but his reply was that he had orders to the contrary, and could not disobey. I did not think he acted from fear or was a coward, but I told him afterward he lost an opportunity that day to make his mark and put a feather in his cap; and I believe he thought so, too, and regretted he had not made a charge regardless of orders.

In a previous chapter, the account was given of the massacre of the little Mexican train and the scattering of their flour and feather beds upon the bluffs near the site of Fort Dodge, but before the fort was established.

On the bottom immediately opposite is where Colonel Thompson’s horses of the troop of the Seventh Cavalry were run off by the Indians. One of the herds on duty jumped into the river and was killed; the other unfortunately or fortunately was chased by the savages right into the parade ground of the fort before the last Indian leaving him, grabbing at his bridle-rein in his determined effort to get the soldier’s horse. The persistent savage had fired all his arrows at the trooper, and the latter, when taken to the hospital, had two or three of the cruel shafts stuck in his back, from the effect of which wounds he died in a few hours.

Major Kidd, or Major Yard, I do not remember which just now, was in command at Fort Larned, and had received orders from department headquarters not to permit less than a hundred wagons to pass the fort at one time, on account of the danger from Indians, all of whom

-101-

were on the warpath. One day four or five ambulances from the Missouri River arrived at the fort filled with New Mexico merchants and traders on the way home to their several stations. In obedience to his orders, the commanding officer tried to stop them. After laying at Larned a few days, the delay became very wearisome; they were anxious to get back to their business, which was suffering on account of their prolonged absence. They went to the commanding officer several times, begging and pleading with him to allow them to proceed. Finally he said: “Well, old French Dave, the guide and interpreter of the post, is camped down the creek; go and consult him; I will abide by what he says.” So, armed with some fine old whisky and the best brand of cigars, which they had brought from St. Louis, they went in a body down to French Dave’s camp, and, after filling him with their elegant liquor and handing him some of the cigars, they said: “Now, Dave, there are twenty of us here, all bright young men who are used to the frontier; we have plenty of arms and ammunition, and know how to use them; don’t you think it safe for us to go through?” Dave was silent; they asked the question again, but he slowly puffed away at his fine cigar and said nothing. When they put the question to him for a third time, Dave deliberately, and without looking up, said: “One man go troo twenty time; Indian no see you. Twenty mans go troo one time and Iridian kill every s-o-b of you.”

General Sheridan was at Fort Dodge in the summer of 1886, making every preparation to begin an active and thorough campaign against the Indians. One day he perceived, at a long distance south, something approaching the post which, with the good field-glass, we took to be a flag of truce-the largest flag of the kind, I suppose, that was ever employed for a like purpose. Little Raven had procured an immense white wagon-sheet and nailed it to one of his long, straight tepee poles, and lashed it

-102-

upright to his ambulance. He marched in with a band of his warriors to learn whether he was welcome, and to tell the big general he would be in the next sleep with all his people to make a treaty. Sheridan told him that maybe he could get them in by the next night, and maybe he had better say in two or three sleeps from now. Little Raven said: “No; all we want is one sleep.” The time he asked for was granted by the general, but this was the last Sheridan ever saw of him until the band made its usual treaty that winter. The wary old rascal used this ruse to get the women and children out of the way before using hostilities. The first time he came after peace was declared he was minus his ambulance. I asked him what had become of it. He replied: “Oh, it made too good a trail for the soldiers; they followed us up day after day by its tracks. Then I took it to pieces, hung the wheels in a tree, hid the balance of it here and there, and everywhere, in the brush, and buried part of it.”

During the same expedition, after the main command had left the fort with all the guides and scouts, there were some important dispatches to be taken to the command. Two beardless youths volunteered to carry them. They had never seen a hostile Indian, or slept a single night on a lonely plain, but were fresh from the states. I knew that it was murder to allow them to go, and I pitied them from the bottom of my heart. They were full of enthusiasm, however, and determined to go. I gave them repeated warnings and advice as to how they should travel, how they should camp, and what precautions to take, and they started. They never reached the command, but were captured in the brush on Beaver creek about dusk one evening-taken alive without ever firing a shot. The savages had been closely watching them, and when they had unsaddled their horses and gone into the brush to cook their supper (having laid down their arms on their saddles), the Indians jumped them, cut their throats, scalped them, and stripped them naked.

-103-

Drunken Tom Wilson, as he was called, left a few days afterward with dispatches for the command, which he reached without accident, just as French Dave had intimated to the New Mexico merchants about one man going through safely. It made Tom, however, too rash and brave. Give him a few canteens of whisky and he would go anywhere. I met him after his trip at Fort Larned one day when he was about starting to Fort Dodge. I said: “Tom, wait until tonight and we will go with you,” but he declined; he thought he was invulnerable and left for the post. On the trail that night, as I and others were going to Fort Dodge, under cover of darkness, our horses shied at something lying in the road as we were crossing Coon creek. We learned afterwards that it was the body of drunken Tom and his old white horse. The Indians had laid in wait for him there under the bank of the creek, and killed both him and his horse, I suppose, before he had a chance to fire a shot.

Two scouts, Nate Marshall and Bill Davis, both brave men, gallant riders, and splendid shots, were killed at Mulberry creek by the Indians. It was supposed they had made a determined fight, as a great many cartridge shells were found near their bodies, at the foot of a big cottonwood tree. But it appears that was not so. I felt a deep interest in Marshall, because he had worked for me for several years; he was well acquainted with the sign language, and terribly stuck on the Indian ways-I reckon the savage maidens, particularly. He was so much of an Indian himself that he could don breech-clouts and live with them for months at a time; in fact, so firmly did he think he had ingratiated himself with them, that he believed they would never kill him. Ed. Gurrier, a halfbreed and scout, had often written him from Fort Lyon not to be too rash; that the Indians would kill anyone when they were at war; they knew no friends among the white men. Marshall and Davis were ordered to

-104-

carry dispatches to General Sheridan, then in the field. They arrived at Camp Supply, where the general was at that time, delivered their dispatches, and were immediately sent back to Fort Dodge with another batch of dispatches and a small mail. When they had ridden to within twenty miles of Fort Dodge, they saw a band of Arapahoes and Cheyennes emerging from the brush on the Mulberry. They quickly hid themselves in a deep cut on the left of the trail as it descends the hill going southwest, before the Indians got a glimpse of them, as the ravine was deep enough to perfectly conceal both them and their horses, and there they remained until, as they thought, the danger had passed.

Unfortunately for them, however, one of the savages, from some cause, had straggled a long way behind the main body. Still the scouts could have made their escape, but Marshall very foolishly dismounted, called to the Indian, and made signs for him to come to him; they would not hurt him; not to be afraid; they only wanted to know who were in the party, where they were going, and what they were after. Marshall imposed such implicit confidence in the Indians that he never believed for a moment that they would kill him, but he was mistaken. The savage to whom Marshall had made the sign to come to him was scared to death; he shot off his pistol, which attracted the attention of the others, who immediately came dashing back on the trail, and were right upon the scouts before the latter saw them. It was then a race for the friendly shelter of the timber on the creek bottom. But the fight was too unequal; the savages getting under just as good a cover as the scouts. The Indians fired upon them from every side until the unfortunate men were soon dispatched, and one of their horses killed; the other, a splendid animal, was captured by the Cheyennes, but the Arapahoes claimed him because they said there were twice as many of them. Consequently,

-105-

there arose a dispute over the ownership of the horse, when one of the more deliberate savages pulled out his six-shooter and shot the horse dead. Then he said: “Either side may take the horse that wants him.” This is generally the method employed by the Indians to settle any dispute regarding the ownership of live property.

As an example of the encounters the soldiers had so frequently with the Indians, in frontier days, there cannot be a better than that of the battle of Little Coon creek, in 1868. I did not take part in this fight, but I was at Fort Dodge at the time, knew the participants, and was present when the survivors entered the fort, after the fray was over. One of the scouts who took part, Mr. Lee Herron, still lives, at Saint Paul, Nebraska, and I am indebted to him for the following account of the fight and the copy of the accompanying song, which he compiled for me, very recently, with his own hand.

FIGHT AT LITTLE COON CREEK

During 1868 the Indians were more troublesome than at any previous time in the history of the old Santa Fe Trail-so conceded by old plainsmen, scouts and Indian fighters at that time. It was a battle ground from old Fort Harker to Fort Lyon, or Bent’s Old Fort at the mouth of the Picketware, near where it empties into the Arkansas River. The old Santa Fe Trail had different outfitting points at the east, and at different periods., At one time it started at Westport, now Kansas City, at an earlier date at Independence, Missouri, and at one time in the fore part of the nineteenth century-at St. Louis, Missouri; but from 1860 to 1867 the principal outfitting point was at Leavenworth, Kansas, and its principal destination in the west was Fort Union and Santa Fe, New Mexico. But Fort Dodge and vicinity was the central point from which most of the Indian raids culminated and depredations were committed. The Indians became so annoying in 1868 that the Barlow Sanderson

-106-

stage line, running from Kansas City, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, found it necessary to abandon the line as there were not enough soldiers to escort the stages through. Also the Butterfield stage line on the Smoky Hill route was abandoned. Several of the southern tribes of Indians consisted of Kiowas, Comanches, Arapahoes, Cheyennes, Apaches and Dog Soldiers. The Dog Soldiers consisted of renegades of all the other tribes and were a desperate bunch, with Charley Bent as their leader. Also the Sioux, a northern tribe, was on the warpath and allied themselves with the southern tribes. In all some five thousand or more armed Indians joined forces to drive the white people off the plains, and it almost looked for a time as though they would succeed, for they were in earnest and desperate. Had they been better armed, our losses would have been much heavier than they were as they greatly outnumbered us. It was a common occurrence for us to fight them one to ten, and often one to twenty or more, but the Indians frequently had to depend entirely upon their bows and arrows, as at times they had no ammunition. This placed them at a disadvantage at long range as their bows and arrows were not efficient over two hundred feet, but at close range, from twenty five to one hundred feet, their arrows were as deadly as bullets, if not more so. So after the stage line was discontinued, a detail was made of the most fearless and determined men of the soldiers stationed at Fort Dodge, as a sort of pony express, which was in commission at night time, as it would be impossible to travel in the daytime with less than a troop of cavalry or a company of infantry, and they had no assurance of getting through without losing a good part of the men, or perhaps the entire troop, and the entire troop would stand a big chance of being massacred. Indeed, in the fall of 1868 -October, I think-I joined Tom Wallace’s scouts and went with the Seventh United States Cavalry and several companies of infantry, Wallace’s scouts and a company

-107-

of citizen scouts, with California Joe in command, all under command of General Alfred Sully, a noted Indian fighter of the early days. The command started south, crossing the Arkansas River just above Fort Dodge. From the time we left the Arkansas River it was a constant skirmish until we reached the Wichita mountains, the winter home of the southern tribes. After we got into the mountains, the Indians crowded us so hard that the whole command was compelled to retreat, and had not the command formed in a hollow square, with all non-combatants in the center, it might have proved disastrous. As it was, a number were killed and some were taken prisoners and burned at the stake and terribly tortured. A very interesting article could be written about this expedition, and I think but a very little is known of it, as there is but a sentence relating to it in history.

Fort Dodge was the pivot and distributing base of supplies in 1868, and thrilling events were taking place all the time. All trains were held up and some captured and burned, and all who were with the train were killed or captured, and the captured were subjected to the most excruciating torture and abuse. I saw one party which was massacred up west of Dodge. Not a soul was left to tell who they were or where they were going, and no doubt their friends looked for them for many years, and at last gave up in despair. I served in the Civil War in Company C Eighty-Third Pennsylvania Volunteers, and we sustained the heaviest losses, numerically of any regiment in the entire Union army, except the Fifth New Hampshire. This is according to war records compiled by Colonel Fox. But there were many times along the old Santa Fe trail where the percentage of losses was greater than in the Civil War. However, there is no record kept of it that I am aware of. Of course in these fights there were but a few men engaged, where in the Civil War there were tens of thousands and many thousands lost their lives, and a few hundred men who lost

-108-

their lives out on the great plains was scarcely known except to those in the vicinity-hundreds of miles from civilization.

On the night of September first, 1868, I was coming from Fort Larned with mail and dispatches when I met a mule team and government wagon loaded with wood, going to Big Coon creek, forty miles east of Fort Dodge, as there was a small sod fort located there, garrisoned with a sergeant and ten men. These few men could hold this place against twenty times their number as it was all earth and sod, with a heavy clay roof, and port-holes all around, and they could kill off the Indians about as fast as they would come up, as long as their ammunition held out. But they were not safe outside a minute. They had been depending on buffalo chips for fuel, as there was no other fuel available, and as soon as the men would attempt to go out to gather buffalo chips, the Indians lying in little ravines of which there was a number close by, would let a shower of arrows or bullets into them. The reason why the men with the wagon whom I have mentioned were going to Big Coon Creek was to take them wood. I told the boys who were with the wagon to under no consideration leave Big Coon creek, or Fort Coon as we called it, until a wagon train came by, and if they would not wait for a wagon train, by all means to wait until it got good and dark, as the Indians are inclined to be suspicious at night time, and not so apt to attack as in daytime. The men, whose names were Jimmy Goodman, Company B, Eleventh United States Cavalry, Hartman and Tolen, Company F, Third United States Infantry, and Jack O’Donald, Company A, Third United States Infantry, imagined I was over-cautious, and started back the afternoon of September fourth, 1868.

I, after parting with them, continued on towards Fort Dodge, where I arrived just before daylight, the morning of September second. After lying down and having a

-109-

much needed sleep, and rest, I, in the evening, went up to Tapan’s sutler store. I noticed the Indian’s signals of smoke in different directions, and I knew this foreboded serious trouble. They signaled by fire at night and smoke by day, and could easily communicate with one another fifty or sixty miles. I had not been at the sutler store long, where I was in conversation with some of the scouts. There were a number of famous scouts at Fort Dodge at that time consisting of such men as California Joe, Wild Bill Hickok, Apache Bill, Bill Wilson and quite a number of others whose names I have forgotten, but I noticed the enlisted men had to stand the brunt of the work. I never could understand why this was and it is a mystery to me, except those scouts of fame were too precious, and soldiers didn’t count for much for there were more of them. While I was standing talking, an orderly came up to me and said the commanding officer wanted to see me at once. It was nearly night at this time. I at once reported to the commanding officer. He informed me that he wanted me to select a reliable man and be ready to start with dispatches for Fort Larned, seventy-five miles east on the wet route, or sixty-five miles east on the dry route. As I had just come in that morning, I thought it peculiar he did not select some of those noble spirits I had just left at the sutler’s store, but it was possible he was saving them up for extreme emergency, but I could not see from the outlook of the surroundings as the emergency would be any more acute than at the present time, as the terms of the dispatch we were to take, if I remember right, were for reinforcements. I selected a man of Company B, Troop Seven, United States Cavalry, named Paddy Boyle, who had no superior for bravery and determination when in dangerous quarters, on the whole Santa Fe Trail. Paddy sleeps under the sod of old Kentucky. For many years he had no peer and few equals as a staunch, true friend and brave man. As luck would have it on this night Boyle selected one of the swiftest and best winded

-110-

horses at the fort, and only for that I would not have been permitted to ever see Fort Dodge again, for that horse, as later will be seen, saved our lives. We had our canteens filled with government whisky before we started: as a prevention for rattlesnake bites, as rattlesnakes were thick in those days, or any other serious event which might occur, and often did occur in those strange days on the Great Plains.

I felt a premonition unusual and Boyle did too, and several of our friends came and bade us good-bye, which was rather an unusual occurrence. I don’t think the commanding officer thought we would ever get through, for Indian night signals were going up in all directions, which indicated that they were very restless.

When we arrived near Little Coon creek we heard firing and yelling in front of us. We went down into a ravine leading in the direction we were going, cautiously approaching nearer where the firing was going on, and made the discovery that the Indians had surrounded what we supposed to be a wagon train. We knew somebody was in trouble and could at this time see objects seated all around on the nearby plains, which proved to be Indians, but as yet we had not been seen by the Indians or, if they did see us, they took us for some of their own party as it was night. They were so busy with the wagon train that they didn’t know we were whites until we went dashing through their midst, whooping and yelling like Comanches, and firing right and left. Instead of being a wagon train as we thought it was, it proved to be the party we last met at or near Big Coon creek with the wood wagon, and we arrived just in time to save them from being massacred. At this time the Indians made a desperate charge, but were repulsed and driven back in good style. When I looked the ground over and saw what a poor place it was to make a fight against such odds, I knew that as soon as it got daylight we were sure

-111-

to lose our scalps, and that at any moment they might get in some good shots on one of their desperate charges, and disable or kill all of us. I suggested that either Boyle or myself try and cut his way through the Indians and go to the fort for assistance. As Boyle had the best horse in the outfit-a fine dapple-grey, the same horse previously mentioned in this article-Boyle said he would make the attempt.

He took a sip from his canteen and then handed it to me, saying we would probably need it more than he would, as he didn’t propose to be taken alive and that if he got through he could drink at the other end of the line. It always seemed to me this noble horse understood the situation and knew what was wanted of him. Our horses had a terrible dread of Indians. When Boyle started it needed no effort to induce the noble dapple-grey to go, for he darted away like a shot out of a gun. When Boyle left us, he had to go down in a deep ravine which was the bed of Little Coon creek, and where the main trail weaved to the right for a distance of perhaps two hundred yards in order to again get out of the ravine, as the banks were very steep and not practicable to go straight across. At this time some of the Indians attempted to head him off, and did so far as following the main trail was concerned, as I had a fairly good view of the top of the hill where Boyle should come out. At this time several shots were fired at Boyle, and not seeing him come out I supposed he was killed and told the men so, and there was no possible chance of us ever getting out that I could see. Up to this time we had been behind the wagon, but the Indians were circling all around us, and I could see we had to get into more secure shelter as all the protection we had was the wagon which was very poor protection from arrows and bullets. Within a short distance of us there was a deep buffalo wallow. When the Indians had quieted down a little, we, by strenuous efforts, pushed the wagon so it

-112-

stood over the buffalo wallow. After getting into the wallow we found conditions much improved so far as shelter from the firing was concerned and if our ammunition was more plentiful we would have felt much more encouraged, but we knew unless relief came before day~ light they would get us. But I will mention a little mat~ ter that perhaps many of the good people of Kansas would not approve of, as Kansas is a prohibition state. The canteen full of whisky did a lot to keep up our spirits. Occasionally I would give each one a small amount and did not neglect myself. This little bit of stimulant, under these extremely unpleasant conditions had a very good effect, and I believe our aim was more steady and effective.

The Indians charged repeatedly, uttering the most blood curdling yells. Most of the time they would be on the side of their horses so we could not see them, but hitting their ponies, the bullets would go through and occasionally get one of them. They several times charged up within a few feet of the wagon, but the boys were calm and took deadly aim and would drive them back every time. There were some of their ponies lying dead close to the wagon. It was seldom the Indians would make such desperate and determined efforts when there was nothing to gain except to get a few scalps, but I think at that time, in fact, at al1. times when they were on the warpath, a scalp-lock was more desirable to an Indian warrior than anything else their imagination could conceive. It was the ones who got the most scalps that were the most honored, and promotion to chiefs depended on the amount of scalps secured while out on expeditions on the warpath. I have known Indians to be cornered when they would make the most desperate fight, and fight until all were killed.

At this time our ammunition was getting low and we saw we couldn’t hold out much longer. Goodman had

-113-

been wounded seven times by arrows and bullets, Jack O’Donald had been struck with a tomahawk and received other wounds, Nolan was wounded with arrows and bullets. This left Hartman and myself to stand off the Indians, and towards the last Hartman was wounded but not seriously disabling him. I would load my Remington revolver and hand it to Nolan, who was obliged to fire with his left hand, his right arm being shattered. The Indians charged right up to the wagons more than once. At one time O’Donald had a hand to hand encounter with one, and was struck on the head with a tomahawk. It was only by the most desperate exertions that anyone escaped. The party were entirely within their power more than once, but they would cease action to carry off their dead-which lost the Indians many a fight, as they thought if one of their number lost his scalp he could not enter the Happy Hunting Grounds.

Finally we saw the Indians apparently getting ready for another rush from a different direction, fully expecting that they would get us if they did. At about the same time I noticed a body of horsemen coming out of a ravine in another direction. We supposed this was another tactful dodge of the Indians and they would come at us from two ways. At this time we hadn’t any prospect or hope of saving our lives. Had we had plenty of ammunition we could have probably held them off for awhile, but ammunition we did not have, perhaps not over a dozen rounds. It was understood by all of us that we would not be taken alive, but that each one’s last shot was to be used on himself.

What seemed extremely mysterious was when the body of horsemen, just previously mentioned, came out of the ravine, the men on the horses seemed to be dressed in white, and as they came on to high ground, deployed a skirmish line. I had seen Indians form a line of battle occasionally, but it was not common for them to do so.

-114-

After they had advanced within three hundred or four hundred feet of us we were still undecided who they were, but they acted and had more the appearance of white men than Indians. But relief we hadn’t the least hope of. It was hard to realize that any assistance could possibly reach us, as there were no scouting parties out that we knew of, and we had every reason to believe Boyle was killed and never reached the fort. This body of men dressed in white halted about three hundred feet from us and stood there like a lot of ghosts. (The reader must remember this was in the night time and we could not make out objects plainly. Had it been daytime we could of course readily have seen who they were).

The suspense at this time was becoming very acute. I told the men I would risk one shot at them and end the suspense. But at this Goodman raised his head and looking in the direction of the horsemen remarked, “I believe they are our own men; don’t fire.” I was about of the same opinion, but the Indians were always resorting to some trickery. I had about made up my mind they were trying to deceive us and make us think they were white men. Finally one of them hollered, speaking in English, that they were friends. But that didn’t satisfy me as the renegade Bent boys were with the Dog Soldiers and could speak good English, and were always resorting to every conceivable form of fraudulent devices to get the advantage of white people. They had been the means of causing the deaths of scores of people in this way.

At this time each one of our party was prepared to take his own life if necessary, rather than to be taken prisoner, for being captured only meant burning at the stake, with the most brutal torture conceivable. We knew we did not have sufficient ammunition to resist another charge, and if we fired what Iittle ammunition we had we would have none to take our own lives with. I hollered to one of the horsemen for one of them to advance. At

-115-

once a horseman came riding up with his carbine held over his head, which those days was a friendly sign. After he came up within about fifty feet, I recognized Paddy Boyle, as though he had risen from the dead. The whole command advanced then and it was a squadron of the Seventh United States cavalry. The joy experienced in being relieved from our perilous position may be imagined. Shaking hands and cheering and congratulations were in full force. Soon after the cavalry arrived, it might have been an hour, another command of infantry came in on a run with wagons and ambulances, and accompanying them was a government doctor; I think his name was Degraw, post surgeon, and a noble man he was. He had the wounded gently cared for and placed in the ambulances and they received the kindest of attention and care in the hospital at Fort Dodge until able to be around, but I don’t think any of them ever recovered fully.

It might be of interest to the reader to know why these horsemen were dressed in white, as I have previously mentioned. It was an ironclad custom in those strenuous and thrilling times for every man to take his gun to bed with him or “lay on their arms,” as the old army term gives it, loaded and ready for action at a moment’s notice, with their cartridge box and belt within their reach. The men those days were issued white cotton flannel underclothes, and as the weather was warm, no time was taken to put on their outside clothes, but every man immediately rushed to the stables at the first sound of the bugle which sounded to horses, and mounted at one blast. When this call was sounded it was known that an extreme emergency was at hand and men’s lives in jeopardy. This white underclothing accounts for the mysterious look of the troopers when they made their appearance at Little Coon Creek, and the mysterious actions of the squadron in not advancing up to us when they first arrived, can be explained that they did not know the situation of affairs,

-116-

as there was no firing at that particular time, and they were using extreme caution for fear they would run into an ambush, of part of the Indians. I think, if I remember rightly, there were four Indians who followed Boyle right up to the east picket line at the fort, and had he had to go a mile farther he never could have made it to the fort. The noble dapple-grey horse, if I remember rightly, died from the effects of the fierce run he made to save our lives.

General Alfred Sully who was at that time in command of the troops in the Department, and who was an old and successful Indian fighter, issued an order complimenting the party on their heroic and desperate defense that they made and also for mine and Boyle’s action in charging through the Indians to their assistance. As there were scores of little skirmishes, and some big ones taking place on the old Santa Fe trail all the time at some portion of it, it was generally conceded that the Little Coon Creek engagement was the most desperate fight for anyone to come out alive. There were probably as desperate ones fought, but none ever lived to tell it. This is the only instance I know of where a General United States Officer had an order issued and read publicly to the troops of the different forts in the Department, commending the participants of a small party in an Indian fight for heroic action. How any of the party ever escaped is a mystery to me today and always has been. It was reported after peace was declared that Satanta, head chief of the Kiowas, admitted that in the Little Coon Creek fight the Indian warrior losses were twenty-two killed besides a number wounded. I did not count the number of times the wagon was struck with arrows and bullets, but parties who said they did count them reported the wagon was struck five hundred times, and I have not a doubt that this is true, for arrows were sticking out like quills on the back of a porcupine, and

-117-

the sideboards and end of the wagon was perforated with bullets. The mules were riddled with bullets. Two pet prairie dogs which the boys had in the wagon in a little box were both killed. The general order which was issued by General Alfred Sully, only mentions four Indians being killed, but these being left on the ground were all that could be seen. It is well known among old Indian fighters that Indians on the war-path and losing their warriors in battle will always carry off their dead if possible. It is very often their custom to tie their buffalo hide lariats around their body or connect with a belt and the other end fastened to their saddle when going into battle, and then if they are shot off their ponies, their ponies were trained to drag them off, or at least until some of their brother warriors came to his assistance, then two would come up, one on each side, on a dead run, reach down and grab him. If he was attached to a lariat, they would cut it in an instant and off they would go, but it was a common thing for the rescuers to get shot in their heroic efforts to save their comrades. I have witnessed proceedings of this kind a number of times, and there have been many instances where two or three warriors would be shot trying to rescue a comrade.

The writer saw the above-mentioned wagon after it was brought into Fort Dodge, and it was literally filled with arrows and bullet holes, and the bottom of the wagon bed was completely covered with blood as were the ends and sides where the wounded leaned over and up against them. I never saw a butcher’s wagon that was any bloodier.

Mr. Herron concludes the story of the fight as follows:

-118-

SONG

Calm and bright shone the sun on the morning,

That four men from Fort Dodge marched

With food and supplies for their comrades

They were to reach Big Coon Creek that day;

‘Tis a day we shall all well remember,

That gallant and brave little fight,

How they struggled and won it so bravely

Though wounded, still fought through the night.

Chorus:

So let’s give three cheers for our comrades,

That gallant and brave little band,

Who, against odds, would never surrender,

But bravely by their arms did they stand.

Fifty Indians surprised them while marching,

Their scalps tried to get, but in vain;

The boys repulsed them at every endeavor,

They were men who were up to their game.

“Though the red-skins are ten times our number,

We coolly on each other rely.” Said the corporal

in charge of the party,

“We’ll conquer the foe or we’ll die!”

Still they fought with a wit and precision;

Assistance at last came to hand,

Two scouts on the action appearing,

To strengthen the weak little band.

Then one charged right clear through the Indians,

To Fort Dodge for help he did go, While the

And gallantly beat off the foe.

A squadron of cavalry soon mounted,

Their comrades to rescue and save.

General Sully, he issued an order,

Applauding their conduct so brave.

And when from their wounds they recover,

Many years may they live to relate,

The fight that occurred in September,

In the year eighteen sixty-eight.

-119-

This song was composed by Fred Haxby, September, 1868, on the desperate fight at Little Coon creek, about thirty miles east of Fort Dodge, on the dry route, September second, 1868. Fred Haxby, or Lord Haxby, as he was called, was from England, and at the time of the fight was at Fort Dodge.

The song gives fifty Indians comprising the attacking party. This was done to make the verses rhyme, as I am sure there were many more than this.

The tune this song was sung by, nearly a half a century ago, was the same as the one which went with the song commonly known at that time, “When Sherman Marched Down to the Sea.” Not, “Sherman’s March Through Georgia.” “Sherman’s March Through Georgia,” and “Sherman’s March to the Sea,” were different songs and different airs.

*The author of this work is further indebted to Mr. Herron for another interesting story of soldier life in the wild days. It runs as follows:

CAPTURING THE BOX FAMILY

Capturing the Box family from the Indians was one of the interesting events which took place at Fort Dodge, although the rescue of the two older girls took place south of Fort Dodge near the Wichita mountains, perhaps near two hundred miles. But the idea of getting the girls away from the Indians originated at Fort Dodge, with Major Sheridan, who, at the time, October, 1866, was in command of the fort. At this time, the troops garrisoning the fort consisted of Company A, Third United States infantry, of which I was a member, holding a non-commissioned officer’s rank.

On a sunshiny day about the first of October, 1866, the sentinel reported what appeared to be a small party of mounted men, approaching the fort from the south

-120-

side of the Arkansas river, perhaps two miles away, and just coming into sight out of a range of bluffs which ran parallel with the river. They proved to be Indians and the glittering ornaments with which each was decorated could be seen before either the Indians or their ponies. After the Indians came down to the river and were part way across, a guard, consisting of a corporal and two men, met them at the north bank of the river, just below the fort, and halted them. It was noticed they carried a pole to which was attached an old piece of what had one time been a white wagon cover, but which at this time was a very dirty white. This was to represent a flag of truce and a peaceful mission, which idea they had got from the whites, though the Indians were very poor respectors of flags of truce. When approached with one by white men, they, on several occasions, killed the bearers of the flag, scalped them, and used their scalps to adorn their wigwams. They considered the flag a kind of joke and rated the bearer as an easy mark.

The guard learned from the Indians that they were Kiowas, old chief Satanta’s tribe. Fred Jones, who was Indian interpreter at Fort Dodge, was requested to come down and ascertain what was wanted The Indians in. formed Jones that they had two pale-faced squaws whom they wished to trade for guns, ammunition, coffee, sugar, flour-really, they wanted about all there was in the fort, as they set a very high value on the two girls.

By instructions of the commanding officer, they were permitted to come into the fort to talk the matter over. After passing the pipe around and each person in council taking a puff, which was the customary manner of procedure, they proceeded to negotiate a “swap,” as the Indians termed it. The Indians wanted everything in sight, but a trade or swap was finally consummated by promising the Indians some guns, powder and lead,

-121-

some coffee, sugar, flour and a few trinkets, consisting mainly of block tin, which was quite a bright, glittering tint. This was used to make finger rings, earrings and bracelets for the squaws. The bracelets were worn on both ankles and arms of the squaws and, when fitted out with their buckskin leggings and short dresses, covered with beads, they made a very attractive appearance.

The Indians knew they had the advantage and drove a sharp bargain-at least, they thought they did. They insisted on the goods being delivered to their camp near the Wichita mountains, which was quite an undertaking, considering that a white man had never been in that section except as a prisoner, a renegade, or possibly an interpreter. Two wagons and an ambulance were ordered to be got ready, and the wagons were loaded. Our party consisted of Lieutenant Heselberger of Company A. Third United States infantry, an old experienced Indian fighter, one non-commissioned officer, (myself), and seven privates, with Fred Jones as interpreter. We crossed the river about a half mile below Fort Dodge and took a southerly course, traveling for days before we came to the Kiowa camp. One evening, just as the sun was going down, we came to a high hill, and as we gained the crest, going in a southeasterly direction, I witnessed the most beautiful sight I ever saw.

The whole Kiowa tribe, several thousands in number, were camped on the banks of a beautiful sheet of water, half a mile away. The sun setting and the sun’s rays reflecting on the camp, gave it a fascinating appearance. Hundreds of young warriors, mounted on their beautiful ponies, and all dressed in their wild, barbaric costume, bedecked with glittering ornaments, were drilling and going through artistic maneuvers on the prairie, making a scene none of us will ever forget. There were about three hundred lodges, all decorated as only an Indian could decorate them, being painted with many gaudy

-122-

colors. Many papooses were strapped upon the more docile ponies, and, under the guidance of some warriors, were getting their first initiation into the tactics necessary to become a warrior; while squaws were engaged in tanning buffalo skins and going through the different movements necessary to a well-organized wild Indian camp. Small fires were in commission in different parts of the camp, with little ringlets of smoke ascending from them, which, in the calm, lovely evening, made an exceedingly interesting scene, while off on the distant hills thousands of buffalo were peacefully grazing.

Right here let me say that I have seen the Russian Cossacks on the banks of the river Volga, in southern Russia, and, while they have the reputation of being the finest and most graceful riders in the world, they did not compare, for fine horsemanship, with the American Indian of fifty years ago.

As we halted and took in this beautiful panorama, a bugle call sounded, clear and distinct, in the Kiowa camp. Three or four hundred young warriors mounted their ponies, the charge was sounded, and they came dashing towards us. On they came, keeping as straight a line as any soldiers I ever saw. When about three hundred feet from us and just as we were reaching for our carbines (for everything had the appearance of a massacre of our little party, and we had determined when starting on this venturesome errand that if the Indians showed treachery, we would inflict all the punishment on them we possibly could before they got us, and would shoot ourselves rather than be captured alive; for being captured meant burning at the stake and the most excruciating torture), the bugle sounded again, the Indians made a beautiful move and filed to right and left of us, half on each flank, and escorted us to their camp which was but a short distance away. The bugler was a professional but we never knew who he was as he never

-123-

showed himself close enough to us to be recognizable, but he was supposed to be some renegade. On other occasions, when a battle was going on, these bugle calls were heard. At the battle of the Arickaree where Roman Nose, head chief of the Cheyennes attacked Forsythe’s scouts, the bugle was heard sounding the calls all through the battle.

The night we arrived at the Kiowa camp we were located on the banks of a creek. The young warriors commenced to annoy us in all manner of ways, trying to exasperate us to resent their annoyances so they could have an excuse to make an attack on us. At this time, Fred Jones and Lieutenant Heselberger, who had been up to Satanta’s lodge, came to our camp and, seeing the taunts and annoyances to which we were being subjected, admonished us not to resent them, for if we did the whole party would be massacred or made prisoners and burned at the stake. Jones, the interpreter, immediately went back to Satanta and reported the situation. Satanta, at once, had a guard of old warriors thrown around us and thus saved us from further annoyances. Not that Satanta was any too good or had any love for us that he should protect us, but at that immediate period it was not policy for him to make any rash movements.

All night long the Indian drums were continually thumping and the Indians were having a big dance in their council chamber, which was always a custom, among the wild Indian tribes, when any unusual event was taking place. The next morning we were up bright and early, teams were hitched to the wagons and proceeded to the center of the Indian camp in front of the council chamber, where the goods were unloaded. The two young girls were then turned over to us by one of the chiefs. They were a pitiful looking sight. They had been traded from one chief to another for nearly a year, and had been subjected to the most cruel and degrading

-124-

treatment. The eldest girl gave birth to a half-breed a short time after their rescue. One of the girls was seventeen and the other fourteen years old. They had been captured near the Texas border and had been with the Indians some time, according to the story told us. The father, a man by the name of Box, the mother, and their four children were returning to their home, when they were overtaken by a band of Indians. The Indians killed Mr. Box because he refused to surrender; the youngest child was taken by the heels and its brain beaten’ out against a tree; the mother and three children were taken back to the main camp. The mother and youngest child were taken to the Apache camp, an Apache chief purchasing them from the Kiowas. We felt confident that, later on, we would get possession of the mother and youngest child, for the Apaches would want to trade too, when they learned how the Kiowas had succeeded. But the articles which were traded to the Kiowas were of very poor quality. The guns were old, disused muzzleloading rifles; the powder had but little strength, having lost its strength and a man would be quite safe, fifty feet away from it when discharged; the lead was simply small iron bars, with lead coating; but the Indians seemed to think it was all right, as they didn’t do much kicking, but people who, in a trade, would take a ten-cent “shinplaster” in preference to a twenty-dollar bill, were easy marks to deal with.

After a long, hard march, we finally arrived again on the banks of the Arkansas River, which we had had little hopes of doing. Knowing the treacherous disposition of the Indians, we expected they would lie in ambush for us, so we were continually on the alert and always went into camp at a location where we had a good view for several rods around us. It took Custer’s whole Seventh United States cavalry, in the winter of ’68 and ’69, to get some white women from the Indians, and the way he succeeded was by getting the head chiefs to hold a treaty, then tak-

-125-

ing them prisoners and holding them until the Indians surrendered the women. Our party’s going into the Indian camp, as we did, was a very hazardous undertaking, and the only reason we ever got back was that the Apaches had the other two members of the Box family, they wanted to trade for them, and they knew if they killed us the trade would be off. Such a foolhardy undertaking was not attempted again, to my knowledge, in the years I was on the plains.

When we arrived at Fort Dodge, we were given a very pleasant reception, and the young ladies received the tenderest care, but were naturally terribly distressed at their terrible sorrow and affliction. General Sherman, at this time, arrived at Fort Dodge. He had been on a tour of inspection of the frontier forts, and was then on his way to Washington. After learning what the commanding officer had done, he instructed him not to send any more details on so hazardous an undertaking, and not to trade any more goods for prisoners, as it would only have the tendency to encourage the Indians to more stealing.

As we expected, a few days after our return to Fort Dodge the sentry reported a party approaching from east of the fort. All that could be seen was the glittering, bright ornaments, dazzling in the sunlight, but shortly, the party approached close enough for it to be seen that they were Indians. They proved to be a party of Apaches, as we expected, chief Poor Bear being with them. When he was informed that the Indians were coming, Major Andrew Sheridan, who was still in command of Fort Dodge, sent the interpreter, Fred Jones, out to meet them and arrange with the head chief, Poor Bear, to come into the fort and hold a council, a customary thing in those days, when a trade was to be made.

Fort Dodge was located on the north bank of the Arkansas River, and was in the shape of a half circle.

-126-

Close to the river was a clay bank about twelve feet high, where were a number of dugouts, with port-holes all around, in which the men were quartered, so that, if the Indians ever charged and took the fort, the men could fall back and retire to the dugouts. On the east side of the fort was a large gate. The officers were quartered in sod houses, located inside the inclosure. When Poor Bear and his warriors came into the fort, Major Sheridan informed them that the great chief, meaning General Sherman, had given instructions that no more goods would be delivered to the Indian camp in trade for white women, but if the woman and daughter were around, a council would be held to determine what could be done. At this, the Indians left for their camp to report progress. In about two weeks, we noticed Indians by the score, crossing from the south side of the river, below the fort about a mile, near where the old dry route formed a junction with the wet route. A guard at once was instructed to notify the Indians that they must not come any nearer the fort than they were, but must camp at a place designated by the commanding officer, nearly a mile below Fort Dodge.

The Indians proved to be Apaches and the whole tribe came in, numbering about two thousand. They had brought along the white woman, Mrs. Box, and her young daughter, expecting to make a big “swap.” There was no intention of giving anything for them, but there was a plot to get the Indians in, gain possession of the chiefs and head men of the Apache tribe, and hold them as hostages until they would consent to surrender the woman and child. It was a desperate and dangerous experiment, for the Indians outnumbered us greatly. I don’t think, at this time, there were over one hundred and seventy-five men, altogether, at Fort Dodge, including civilians, and against these was one of the most desperate tribes on the plains. When the time arrived for the council, about a hundred of the chiefs, medicine men, and leading men

-127-

of the Indians were let in through the big gate at the east side of the fort. As soon as they were inside, the gate was closed. When they were all ready for the big talk, and the customary pipe had been passed around, Major Sheridan instructed the interpreter to inform the Indians that they were prisoners, and that they would be held as hostages until Mrs. Box and her daughter were brought in and turned over to him.

The Indians jumped to their feet in an instant, threw aside their blankets, and prepared for a fight. Prior to the time the Indians were admitted into the fort inclosure, the mountain howitzers had been doubled-shotted with grape and canister, the guns being depressed; so as to sweep the ground where the Indians were located. Some of the soldiers were marching back and forth, with guns loaded and bayonets fixed, while a number of others, with revolvers concealed under their blouses, were sitting around watching the proceedings. The main portion of the garrison was concealed in the dugouts, the men all armed and provided with one hundred rounds of ammunition per man. The Indians were all armed with tomahawks which they had carefully concealed under their blankets. When they were informed that they were prisoners, they made a dash for the soldiers in sight, as they were but few, the majority, as has been said, being hid in the dugouts; but when the men came pouring out of the dugouts and opened fire, the Indians fell back and surrendered. One of the old chiefs was taken up on the palisades of the fort and compelled to signal to his warriors in their camp. In less than thirty minutes Mrs. Box and her child were brought to the big east gate, and one of the most affecting sights I ever witnessed was that of the mother and girls as they met and embraced each other. It was a sight once seen, never to be forgotten.

Major Sheridan then told the interpreter to inform the Indians that they could go, warning them not to steal

-128-

any more women or children. But the warning was of no avail, for the next two years the frontier was terribly annoyed by Indian raids and depredations.

There were but few fatalities when the soldiers opened fire on the Indians at the fort, as it was done more to intimidate than to kill. A representative of Harper’s Weekly was at Fort Dodge, at the time, and took a number of photographs of the Indians and the Box family, but if there are any of the pictures in existence today, I am not aware of it, but I should like to have them if they exist. This piece of diplomacy on the part of the commanding officer of Fort Dodge cost scores of lives afterwards, for those Apaches went on the war-path and murdered every person they came across, until the Seventh United States cavalry caught up with and annihilated many of them, in the Wichita mountains, in November, 1868.

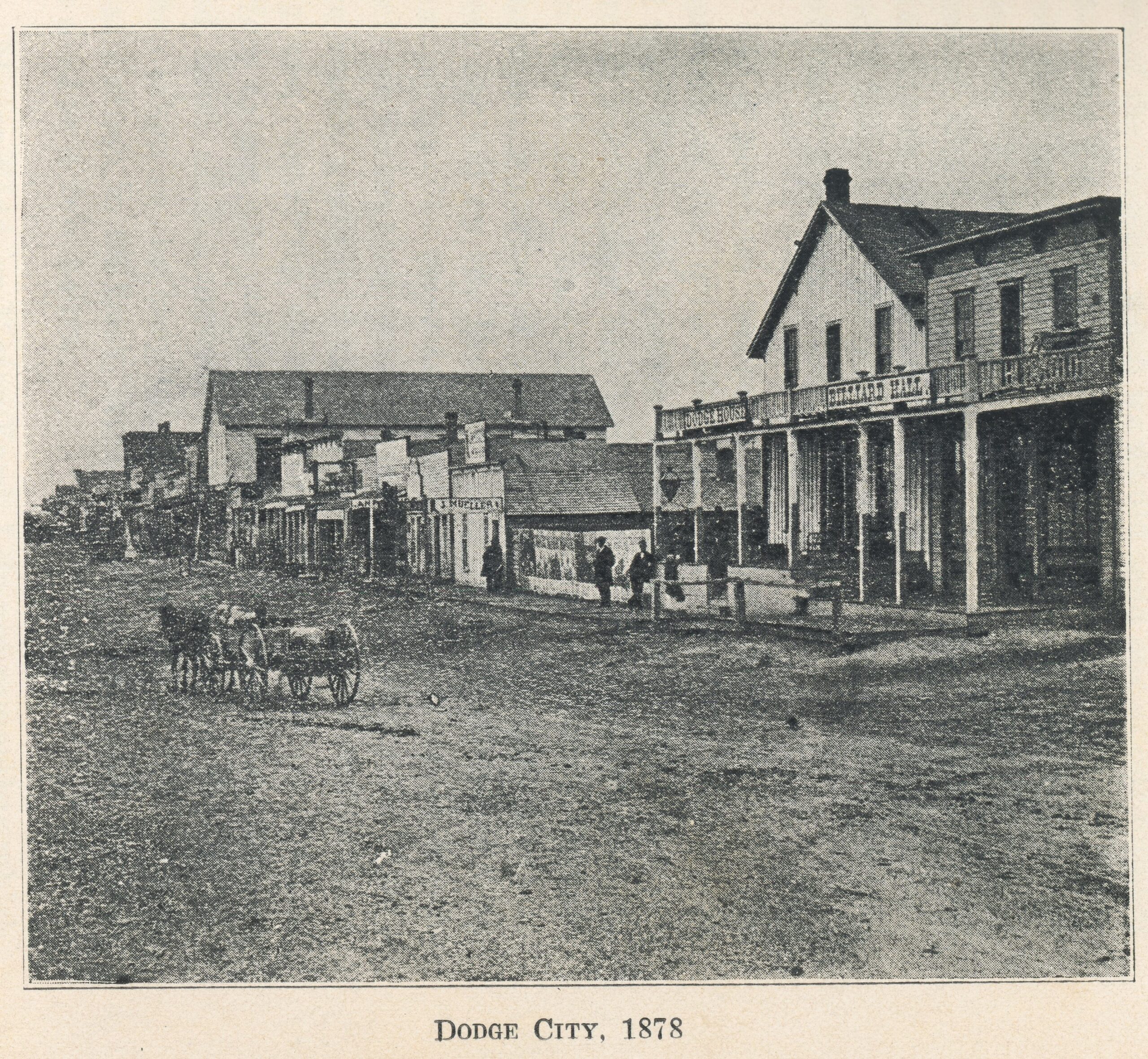

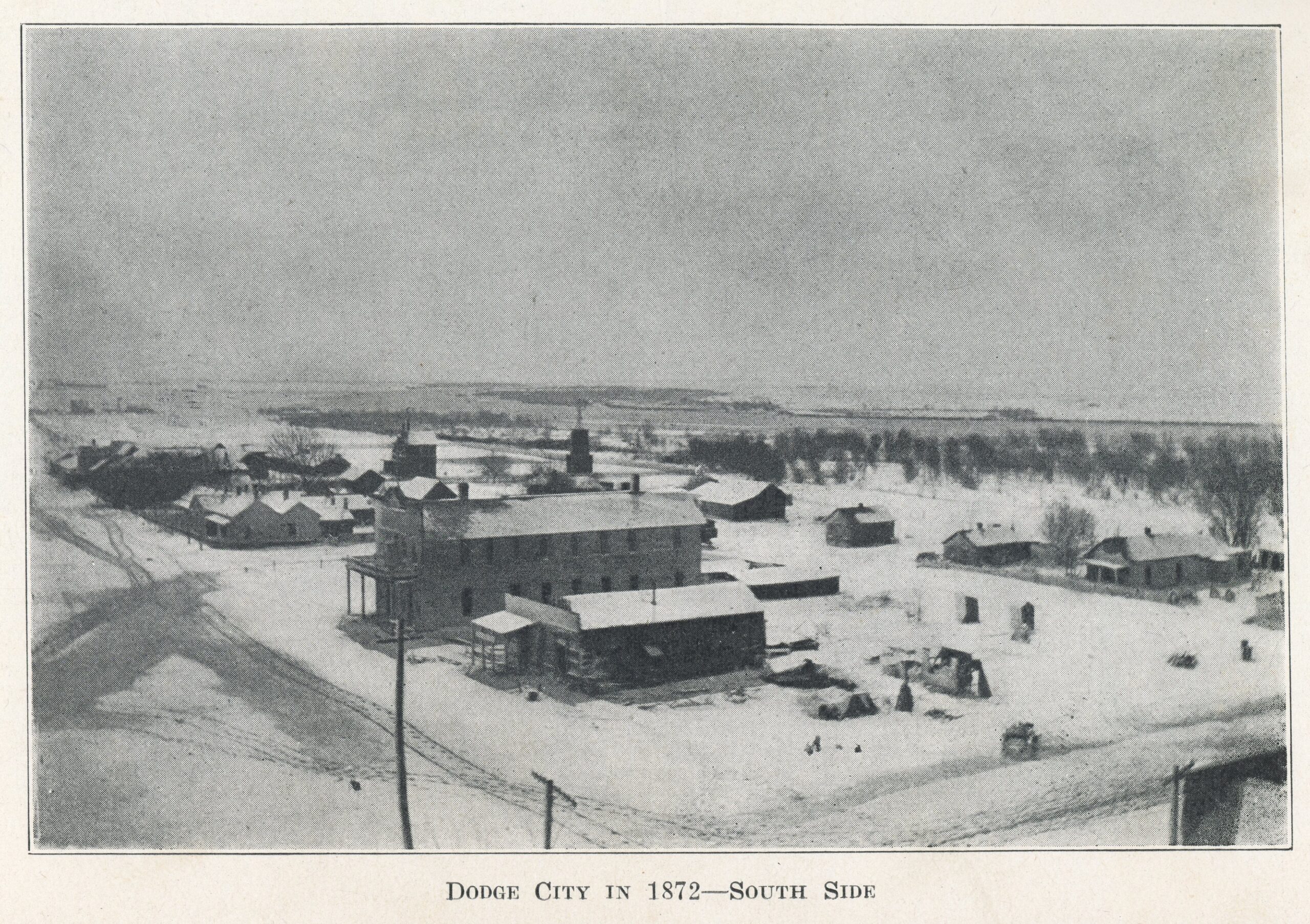

All the great expeditions against the Indians, horse thieves, and bad men were organized and fitted out at Fort Dodge or Dodge City, because, as I remark elsewhere, they were at the edge of the last great frontier or the jumping-off place, the beginning and the end-the end of civilization, and the beginning of the badness and lawlessness of the frontier. Here civilization ended and lawlessness began.

This gave rise to and the necessity for many great and notable men coming to Dodge, such as Generals Sherman, Sheridan, Hancock, Miles, Custer, Sully, and many others, even including President Hayes. Dodge was acquainted with all of these, besides dukes and lords from over the water, who came out of curiosity. We feel proud that she knew these men, and General Miles told the writer that Fort Dodge should have been made one of our largest forts, at least a ten-company post. But he did not take in the situation in time, as it was the key to all the country south of us, and, had it been made a ten-

-129-

or twelve-company post, one can easily see how the garrison could have controlled all the Indian tribes south, who were continually escaping from their agencies and going north, to visit, intrigue, and combine with the northern Indians, the northern tribes doing the same thing when they went south. The troops could have intercepted the Indians either way, and cut them off and sent them back before they were able to do any devilment. Particularly could this have been done when Dull Knife and Wild Hog made their last raid through Kansas. There were only about seventy-five warriors, besides their women and children, in this little band, but they managed to make a laughing stock and a disgrace of our troops; at least, so it appeared from the actions of the officers who were sent after them.

In September, 1868, at the Darlington Agency, there were, under the leadership of Wild Hog and Dull Knife, a small bunch of Cheyenne Indians, who had been moved from their northern agency and, for various reasons, were determined to go back, much against the wishes and orders of the United States government and also their agent, who positively forbade their going. They had secretly been making preparations for this tramp, for some time, but they had no horses, but few guns and ammunition, and very little provisions of any kind. Now, under these adverse circumstances, they stole away.

As has been said, there were only seventy-five warriors all told, outside of their women and children. Their first care was to get themselves mounts, then arms and ammunition, and provisions. Little by little, they stole horses and picked up guns and ammunition from the cattle camps and deserted homes of the frontier settlers, so, when they got within forty miles of Fort Dodge, south, they were supplied with horses, and fairly well supplied with their other wants.

-130-

On Sand Creek, they were confronted with two companies of cavalry and several parts of companies of infantry, with wagon transportation. These soldiers outnumbered the Indians nearly three to one; besides, quite a lot of settlers and some cowboys had joined the troops. To be sure, the settlers were poorly armed, but they were of assistance, in some ways, to the troops.

On their march, the Indians had scattered over a large scope of country. That is, the warriors did, while the women and children kept straight on in the general direction they wanted to go. But the warriors raided and foraged some fifteen or twenty miles on either side of the women and children, and at night they would all rendezvous together. This gave rise to the erroneous impression that the band was very much larger than it was. In fact, there were supposed to be several hundred warriors, and this reckoned greatly in their favor. The bold daring front that they assumed was another big thing in their favor, and made the troops and others believe there were many more of them than there were. When they were confronted with the troops on Sand Creek, they stopped in the bluffs and fortified, while the troops camped in the bottom to watch their movements and hold them in check. But the cowboys said that the Indians only stopped a short time, and, when night came, they broke camp and left the troops behind. The soldiers did not find this out for nearly two days, and, in this maneuver, they had nearly two days the start of the soldiers.

The Indians, next day, trailed by Belle Meade, a little settlement, where they were given a fine beef just killed. Strange to say, they disturbed no on here, except taking what arms they could find and some more “chuck”. Up to this time, they had killed only two or three people. Starting off, they saw a citizen of Belle Meade, driving a span of mules and wagon, coming home.

-131-

They killed him and took his mules and harness, after scalping him. This was done in sight of the town. A few miles further on, they espied another wagon, and, after chasing it within ten miles of Dodge, the driver was killed and his mules and harness taken; and so on. They raided within a few miles of Dodge. Twelve were seen four miles west of Dodge, on an island, where they plundered and burned a squatter’s house. The Dodge people had sent out and brought everyone in for miles around, which is the reason, I suppose, the Indians did not kill more people close to Dodge.

I here quote largely from an enlisted man, stationed at Fort Supply, more than a month after this Indian raid through Kansas and Nebraska was over, so he had time to look calmly over the situation, and the excitement had died down. As his views and mine are so nearly alike, I give the most of his version. He says:

“Field-marshal Dull Knife outgeneraling the grand pacha of the United States army, and reaching, in safety, the goal of his anticipations, being, it is said, snugly ensconced among his old familiar haunts in Wyoming and Dakota. Without casting the least reflection upon or detracting a single thing from the ability, loyalty, or bravery of our little army, it must be said, that the escape of Dull Knife and his followers, from the Cheyenne Agency, and their ultimate success in reaching Dakota territory, is certainly a very remarkable occurrence in the annals of military movements. I have no definite means of giving the exact number of Dull Knife’s force, but, from the most reliable information, it did not exceed one hundred warriors (this is about Agent Mile’s estimate). Dull Knife’s movements, immediately after he left the reservation, were not unknown to the military authorities. He was pursued and overtaken by two companies of cavalry, within sixty miles of the agency he had left. He there gave battle, killing three soldiers,

-132-

wounding as many more, and, if reports of eye witnesses are to be believed, striking terror into the hearts of the remainder, completely routing them. All the heads of the military in the Department of the Missouri were immediately informed of the situation, and yet, Dull Knife passed speedily on, passing in close proximity to several military posts, and actually marching a portion of the route along the public highway, the old Santa Fe trail, robbing emigrant trains, murdering defenseless men, women, and children as their fancy seemed to dictate, and, at last, arriving at their destination unscathed, and is, no doubt, ere this, in conference with his friend and ally, Sitting Bull, as to the most practicable manner of subjugating the Black Hills.

“While we look the matter squarely in the face, it must be conceded that Dull Knife has achieved one of the most extraordinary coup d’etat of modern times, and has made a march before which even Sherman’s march to the sea pales. With a force of a hundred men, this untutored but wily savage encounters and defeats, eludes, baffles, and outgenerals ten times his number of American soldiers. At one time during his march, there were no less than twenty-four companies of cavalry and infantry in the field against him, and he marched a distance of a thousand miles, almost unmolested. Of course, most of the country he passed through was sparsely settled, but, with the number of military posts (six), lying almost directly in his path, and the great number of cattle men, cowboys, freighters, etc., scattered over the plains, that came in contact with his band, it does seem strange that he slipped through the schemes and plans that were so well laid to entrap him. However, Dull Knife has thoroughly demonstrated the fact that a hundred desperate warriors can raid successfully through a thousand miles of territory, lying partly in Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, and the Indian Territory, steal stock, and perpetrate outrages too vile and horrible to print;

-133-

and this in the face of ten times their number of well-equipped United States troops. That some one is highly reprehensible in the matter of not capturing or annihilating Dull Knife and his entire band is believed by all, but who the culpable party is will probably never be placed on the pages of history.

“The cause that led to the outbreak is the same old story-goaded into desperation by starvation at the hands of the Indian agents. There are no buffalo anywhere near the agency, and this same band were allowed, last fall and winter, to go from their reservation to hunt, to supply themselves with meat. They did not find a single buffalo. A portion of them killed and ate their ponies, and the remainder feasted on their dogs. An Indian never eats his dog except when served up on state occasions, and their puppies are considered a great delicacy. They only feed these to their distinguished guests, at great night feasts. They consider they are doing you a great honor when they prepare a feast of this kind for you, and they are badly hurt and mortified if you do not partake freely of same. Dull Knife appealed so persistently for aid, the commanding officer ordered a few rations to be given them (which military establishments have no authority to do). These were eagerly accepted and greedily devoured.

“After soldiering, as a private, ten years on the plains, I am convinced that a majority of the Indian raids have been caused by the vacillating policy of the government, coupled with the avaricious, and dishonest agents. I do not pretend to hold the Indian up as an object of sympathy. On the contrary, I think they are treacherous, deceitful, black-hearted, murdering villains. But we should deal fair with them and set them an example for truthfulness and honesty, instead of our agents, and others in authority, being allowed to rob them. Two wrongs never made a right, and no matter

-134-

what wrongs they have committed, we should live strictly up to our promises with them.”

I will give only a brief account of this raid through our state, from my own memory. I was on my way to Boston to sell a lot of buffalo robes we had stored there. At Kansas City I received a telegram from my firm, saying, “Indians are out; coming this way; big Indian war expected.” I returned to Dodge at once, found everything in turmoil, and big excitement. After getting the news and advice from Colonel Lewis, commander of Fort Dodge (who was well posted, up to that time, in regard to the whereabouts of these Indians, though he had no idea of their number, supposing them to be a great many more than there were), William Tilghman, Joshua Webb, A. J. Anthony, and myself started southwest, thinking to overtake and join the troops already in the field. We made fifty miles that day, when we met a lot of farmers coming back. They said the Indians made stand against the soldiers, in the bluffs on Sand Creek. The soldiers camped a short distance down the creek, for two days, when they made a reconnaissance and found the Indians had been gone for nearly two days, while the troops thought they were still there and were afraid to move out. But it seems the Indians broke camp the first night, and were nearly two days’ march ahead of the troops, Captain Randebrook in command, trailing on behind them.

Before our little company started, Colonel Lewis requested me to report to him immediately upon our return, which I did. When he heard the story of the cowboys and settlers who were on Sand Creek with the trpops, and how cowardly the officers had acted in letting the Indians escape them when there was such a fine opportunity to capture them, Colonel Lewis was utterly disgusted. I never saw a more disgusted man. He didn’t swear, but he thought pretty hard, and he said: “Wright,

-135-

I am going to take the field myself and at once, and, on my return, you will hear a different story.” Poor fellow! He never returned. The troops just trailed on behind the Indians, when they crossed the Arkansas, and followed on, a short distance behind them, until Colonel Lewis joined them and took command.

And now I’ll tell the story, as told to me, about the killing of Colonel Lewis, as gallant an officer as ever wore a sword. The troops, with Colonel Lewis in command, overtook the Indians this side of White Woman creek, and pressed them so closely they had to concentrate and make a stand. Lewis did the same. Late in the afternoon, he made every arrangement to attack their camp at daybreak next morning, having posted the troops and surrounded the Indians as near as possible. Colonel Lewis attended to every little detail, to make the attack next morning a success, and they were to attack from all sides at the same time, at a given signal. About the last thing he did, before going to headquarters for the night, he visited one of the furthest outposts, where a single guard was concealed. Colonel Lewis had to crawl to get to him. The guard said the Colonel was anxious to shoot an Indian who was on post and very saucy. The guard said, “Colonel, you must not raise up. These out posts sharp shooters are just waiting for us to expose ourselves, and that fellow is acting as a blind, for others to get a chance at us.” But the Colonel persisted. He said he wanted to stir them up; and, just as he rose up, before he got his gun to his shoulder, he was shot down.

They had to crawl to Colonel Lewis and drag him out on their hands and knees. The surgeon in charge knew he would die, and started with him at once for Fort Wallace, but he died before reaching that post. This happened about dark, and the news soon spread throughout the camp-Colonel Lewis was killed-which had a great demoralizing effect upon the troops, as they knew he was a brave man and liked him and had great confidence in

-136-

his ability. His orders were never carried out, and the attack was not made. The Indians broke camp and marched away next morning, but, from the signs they left behind, it was very evident they would not have made much of a fight. Indeed, I have been told there was a flag of truce found in their camp. This was vouched for by several, and there were evidences that they intended to surrender, and it is the opinion of the writer they intended to surrender. Anyhow, I do think, if Colonel Lewis had lived, they would have been so badly whipped they never would have got any further north, and the lives of all those people, who were killed on the Sappa and after they crossed the Missouri, Pacific Railroad, would have been saved. I think they killed about forty people, after they left White Woman creek. The farmers and citizens, who were along with the soldiers, censure the two cavalry captains severely and claim they acted cowardly, several times and at several places. They, I believe, were both tried for cowardice, but were acquitted after a fair trial.

Our citizens of Dodge City, as well as his brother officers and the enlisted men under his command, held Colonel Lewis in great respect, as the following resolutions, presented by the enlisted men, assembled in a meeting for the purpose, at the time of his death, will show:

“Whereas, the sad news has been brought to us of the death, on the field of battle against hostile Indians, of our late commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel William H. Lewis, Nineteenth United States infantry;

“Be it resolved, that his death is felt as a great calamity to the army of the United States, as well as for his family, to whom we tender our most heartfelt sympathy, and that we deplore, in his demise the loss of one of the kindest, bravest, and most impartial commanders to be found in the service;”

-137-

“And be it further resolved, that these resolutions be published in the ‘Army and Navy Journal,’ the Washington and Leavenworth papers, the ‘Ford County Globe,’ and the ‘Dodge City Times,’ and a copy be sent to his relatives.

“THOMAS G. DENNEN,

“Ordnance Sergeant, President,

“LOUIS PAULY,

“Hospital Steward, Secretary.”

The meeting then adjourned.

The old servant, who had been with Colonel Lewis for many years and was greatly attached to him, could not be comforted after his master’s death. He wept and mourned as if he had lost a near relative. After the Colonel had received his mortal wound and knew that he must die, he instructed his attendants to tell the old servant to go to his mother’s, where he would find a home for the balance of his days. Accordingly, after all the business at Fort Dodge had been settled, he started, with a heavy heart, for his new home. He said he knew he would have a nice home in which to spend his last days, but that would not bring his old master back. There is nothing that speaks plainer of the true man, than the disinterested devotion of his servants.

Long years afterwards, when the veterans of the Civil War, living at Fort Dodge, organized a post of the Grand Army of the Republic, they named it the Lewis Post, in honor of the brave but unfortunate Colonel.

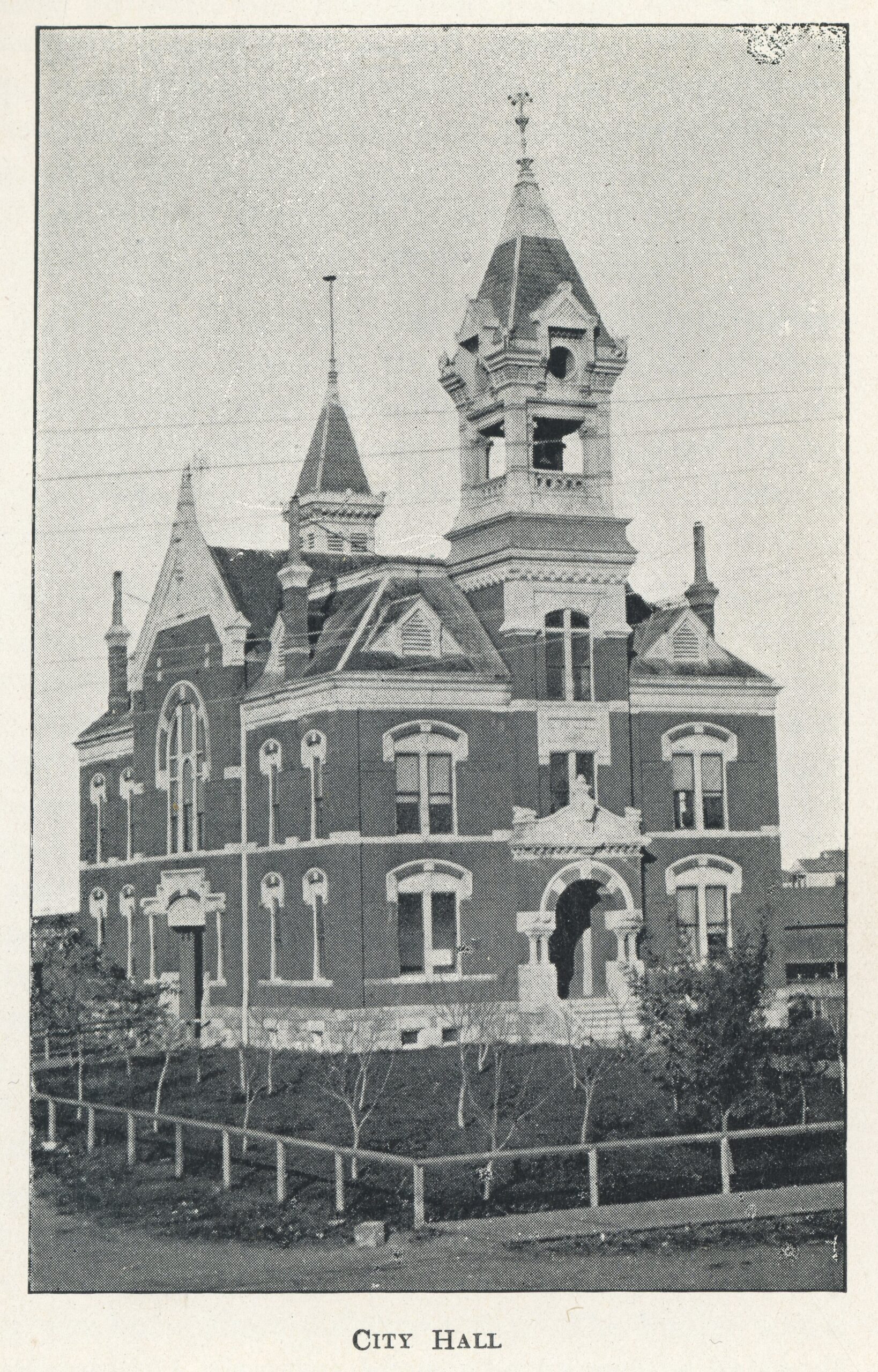

Referring again to the subject of General Miles’ opinion that Fort Dodge should have been at least a ten company post, it might be added that the General, with that very purpose in mind, visited the fort, several years after its abandonment. I was living there at the time, being appointed by the government to take charge of the property left there, and see to the care of the buildings.

-138-

I drove him down, and he took lunch with me. He said:

“Wright, your Dodge people made a big mistake when you placed your smallpox patients in the old hospital.” You see, Dodge City was visited once with smallpox, and it raged- pretty strongly. A great many of our people took it, and it was so violent and virulent that it carried off not a few. Mayor Webster seized the old military hospital and had the patients quarantined in it.

The General further said: “I see Fort Dodge’s great military importance, and I would like to garrison it to its full capacity and would do so; but, Wright, you know, if a single soldier died there from smallpox, even years from now, the press of the country would get up and howl, and censure me ever so severely for subjecting the army to this terrible disease. I can’t afford to take such chances.” General Miles was right; this is just what would have been done, if the smallpox had ever broken out.

-139-