From the nature and habits of the buffalo hunters as already described, and from the fact of his having figured so extensively in all these stories of frontier life, it will readily be seen that the buffalo hunter was closely identified with every phase of existence, of that period and locality. Indeed, for many years, the great herds of buffalo was the pivot around which swung the greater part of the thrilling activities of the plains in early days.

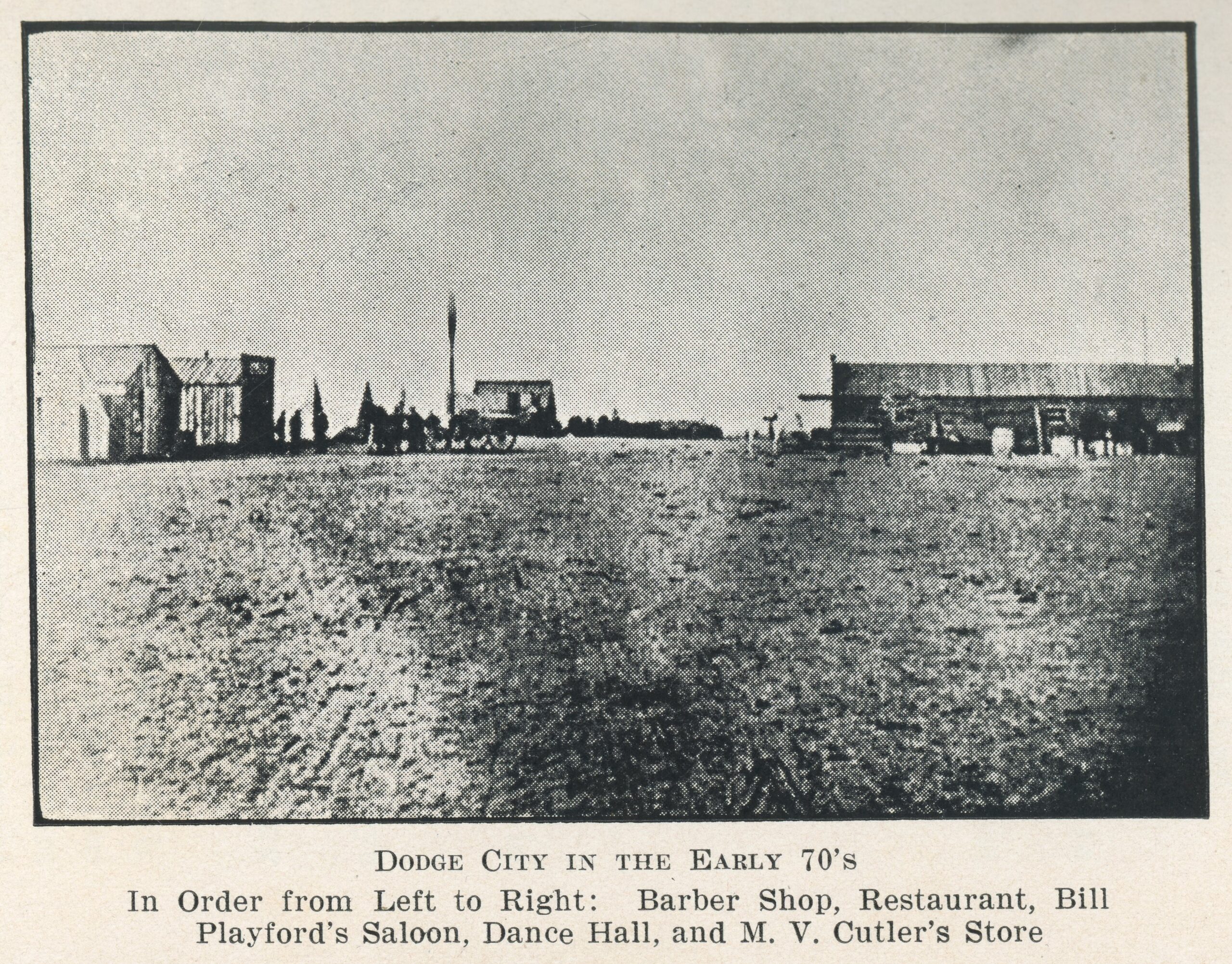

When the railroad appeared the shipping of buffalo hides and meat had much to do with the immense trade that immediately sprang up in frontier towns like Dodge City.

With the removal of the buffaloes from the range, room was made for the cattleman who immediately followed with his wide-stretching and important industry. And, again, the passing of the buffalo herds, at the hands of the white men, was one of the prime causes of Indian hostility, and the keynote of their principal grievance against the whites, and its resulting atrocities and bloodshed.

In a former chapter, I endeavored to give an idea of the size of the buffalo herds of early days. I here give a clipping from the Dodge City Times, of August 18th, 1877, in support of my estimate of the great number of buffaloes on the plains at that time:

TERRIBLE SLAUGHTER OF BUFFALO

“Dickinson County has a buffalo hunter by the name of Mr. Warnock, who has killed as high as 658 in one winter.-Edwards County Leader.

“O, dear, what a mighty hunter! Ford County has twenty men who each have killed five times that many in one winter. The best on record, however, is that of Tom

-189-

Nickson, who killed 120 at one stand in forty minutes, and who, from the 15th of September to the 20th of October, killed 2,173 buffaloes. Come on with some more big hunters if you have any.”

This slaughter, of course was resented by the Indians and the conflicts between them and the hunters were fierce and frequent. In fact, the hunters were among the most intrepid and determined of Indian fighters, and were known as such. In John R. Cook’s remarkable book, “The Border and the Buffalo,” remarkable not only for its wonderful stories of Indian fights and terrible suffering from thirst, but remarkable also for its honest truthfulness, he says: “That noble band of buffalo hunters who stood shoulder to shoulder and fought Kiowas, Comanches, and Staked Plains Apaches, during the summer of 1877, on the Llano Estacado, or the Staked Plains of Texas.”

This refers to a body of men, largely from Dodge City, and Charles Rath and myself among the latter, who previously located in that country. On our arrival, we camped on a surface lake whose waters were from a June waterspout or cloud-burst, and now covered a surface of about five acres of ground, Lieutenant Cooper’s measurement. In the center of the basin it showed a depth of thirty-three inches. Here we witnessed a remarkable sight. At one time, during the day, could be seen horses, mules, buffaloes, antelope, coyotes, wolves, a sand hill crane, negro soldiers, white men, our part Cherokee Indian guide, and the Mexican guide, all drinking and bathing, at one and the same time, from this lake. Nearly all these men were from Dodge City; that is why I mention them, and you will hear of their heroic deeds of bravery and suffering further along.

Outside of a tented circus, that mentioned was one of the greatest aggregations of the animal kingdom, on so small a space of land and water. One can imagine

-190-

what kind of water this must have been when taking into account that nearly a month previous it had suddenly fallen from the clouds, upon a dry, sun parched soil with a hard-pan bottom, being exposed to a broiling hot sun about sixteen hours of every twenty-four, while the thermometer was far above one hundred degrees Fahrenheit, and an occasional herd of buffaloes standing or wallowing in it, not to mention the ever coming and going antelope, wild horse, wolves, the snipe, curlew, cranes and other wild fowl and animals, all of which frequented this. place for many miles around. And yet, we mixed bread, made coffee, and filled our canteens as well as our bellies with it. And yet again, there were men in our party who, in six more days would, like Esau, have sold their birthright for the privilege of drinking and bathing in this same decoction. This was on the Staked Plains – Llano Estacado.

The spring of 1877, the Indians had got very bold. They raided the Texas frontier for hundreds of miles, not only stealing their stock but burning the settlers’ homes and killing the women and children, or carrying them into captivity which was worse than death. Captain Lee, of the Tenth cavalry, a gallant, brave officer and Indian fighter, had rendered a splendid service by breaking up and literally destroying a- band of Staked Plains Indians, bringing into Fort Griffin all the women and children and a number of curiosities. As these In-‘ dians got all their supplies through half-breed Mexicans, strange to say, all these supplies came from way down on the Gulf of California, hundreds of miles overland. And I will interpolate here, that these Indian women and children never saw a white man before they were captured.

Captain Lee, at one time, commanded Fort Dodge, and was stationed there a long time. While he was a brave and daring officer and did great service, it resulted

-191-

in stirring up these Indians, making them more revengeful, villainous, and bloodthirsty than ever. They now began to depredate on the hunters, killing several of the best and most influential of them, and running off their stock. This the hunters could not stand, so they got together at Charles Rath’s store (a place they named “Rath,” and, as I said before, most of these hunters had followed Rath down from Dodge City), and organized. There were not more than fifty of them, but my, what men! Each was a host within himself. They feared nothing and would go anywhere, against anything wearing a breech-clout, no matter how great the number. I do not give the names of these brave men because I remember but a few of their names and, therefore, mention them collectively.

This little band of brave men were treated liberally by the stock men, those who had lost horses by the Indian raids. They were given mounts, and these stock men also gave the hunters bills of sale to any horses of their brand they might capture. They knew to encourage these men and lend them assistance was protecting their frontier.

The hunters chose Mr. Jim Harvey, I think, for their captain, and they chose wisely and well. They organized thoroughly and then started for the Indians. They had a few skirmishes and lost a few men, and also went through great hardships on account of hunger, thirst, cold and exposure, but they kept steadily on the trail. You see, these hardy men had all the endurance of the Indian, could stand as much punishment in the way of hunger, thirst, and cold, were good riders, good shots, and superior in every way to the Indians.

Finally, they discovered about where the main camp of the Indians was, about the middle of March, 1877. The trail got warm, and they knew they were in close proximity to the main camp at some water holes on the Staked Plains. This country was new to the hunters and they

-192-

knew they were up against a big band of Indians. Nevertheless, they were determined to fight them, no matter at what odds.

In the afternoon they discovered an Indian scout.

Of course, they had to kill him; if he escaped he would warn the camp. Now then, after this happened, the hunters were obliged to use due diligence in attacking the camp because when the Indian scout did not turn up in a certain time, the Indians’ suspicions would be aroused. The hunters expected to discover the camp and attack just before day, but they had difficulty in finding the camp in the night. Long after midnight, however, the hunters’ scouts got on to it, but by the time the scouts got back to the boys and reported, notwithstanding they made great haste, it was after sunrise before the hunters got to it. This frustrated all their plans, but the hunters attacked them gallantly and rode into sure range and opened fire. Unfortunately, nearly the first volley from the Indians one of the hunters was shot from his horse and another had his horse killed under him and in falling broke his wrist, while their main guide, Hosea, was shot through the shoulder. Thus handicapped with three badly wounded men from their little band, one having to be carried back on a stretcher which required three or four men, all under a murderous fire, no wonder they had to retreat back to the hills, but fighting every step of the way. And, if I remember rightly, the Indians afterwards acknowledged to Captain Lee, that they lost over thirty men killed outright, and a much larger number wounded, and they abandoned everything to get away with their women and children. They abandoned, on their trail, several hundred head of horses.

Now these forty hunters were fighting three hundred warriors. It was a most wonderful fight and broke the backbone of the Indian depredations. There were only a few raids made after this, and I quote from Cook who says:

-193-

“There was a bill up in the Texas legislature, to protect the buffalo from the hunters, when General Sheridan went before that body and said: ‘Instead of stopping the hunters, you ought to give them a hearty, unanimous vote of thanks, and give each hunter a medal of bronze with a dead buffalo on one side and discouraged Indian on the other. These men/have done more: in the last two years, and will do more in the next year to settle the vexed Indian question, than the regular army has done in the last thirty. They are destroying the Indians’ commissary, and it is a well-known fact that an army, losing its base of supplies, is placed at a great disadvantage. Send them powder and lead, if you will, but, for the sake of peace, let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with cattle and the cowboy, who follows the hunter as a second forerunner of an advanced civilization.'”

How literally true his prediction has become!

Naturally, the affairs and movements of the hunters was the foundation for much of the news of the day, at this period. The following is a common newspaper item in 1878:

“Messrs. T. B. Van Voorhis, J. A. Minor, H. L. Thompson, Ira Pettys, George W. Taylor, Frank Van Voorhis, Frank Harder, and D. C. Macks, all residents of the eastern portion ofFord County, arrived in the city last Tuesday after an absence of seven weeks on a hunting expedition through the southern country. While hunting on the Salt Fork of Red River the party found a span of mules that had been stollen from Van Voorhis last July. They were in possession of Milton Burr who had purchased them of Chummy Jones who is now in hell, if there is such a place. Mr. Burr, upon hearing the evidence of the claimant promptly turned the mules over to the owner who brought them home with him. One of

-194-

the party informed us that he saw a couple of animals that were stolen from Mr. Hathaway but when he went to identify them they could not be found.

“Some of the party called at Mr. Dubb’s camp and found him and Mr. Stealy doing well. They were camped on Oakes Creek, eight miles this side of Red. River and had killed about 1,500 buffaloes. They have a nice lot of meat and hides. Mr. Dubbs asked the party to remember him to his friends in Dodge City.”

Another newspaper item very much to the point, since it gives an excellent description of the mode of killing and preparing the buffalo for market, is entitled, “Slaughtering the Buffalo,” and is from a “Shackelford County (Texas) Letter to the Galveston News.” It follows verbatim:

“The town of Griffin is supported by buffalo hunters and is their general rendezvous in this section. The number of hunters of the ranges this season is estimated at 1,500. We saw at Griffin a plat of ground of about four acres covered with buffalo hides spread out to dry, besides a large quantity piled up for shipment. These hides are worth in this place from $1.00 to $1.60 each. The generally accepted idea of the exciting chase in buffalo hunting is not the plan pursued by the men who make it a regular business. They use the needle gun with telescope, buy powder by the keg, their lead in bulks and the shells and make their own cartridges. The guns in a party of hunters are used by only one or two men, who say they usually kill a drove of thirty or forty buffaloes on one or two acres of ground. As soon as one is killed the whole herd, smelling the blood, collect around the dead body, snuffing and pawing up the ground and uttering a singular noise. The hunter continues to shoot them down as long as he can remain concealed or until the last animal ‘bites the dust.’ The buffalo pays no attention to the report of the gun, and flees only at

-195-

the sight or scent of his enemy. The others of the party then occupy themselves in ‘peeling.’ Some of these have become so skillful they offer to bet they can skin a five- or six-year-old bull in five minutes. The meat is also saved and sent to market and commands a good price.”

We mention this special article because these hunters were all from Dodge City, formerly, and they drifted south along with the buffalo.

The Llano Estacado, or Staked Plains, in Texas, which has been mentioned as the scene of a particularly fierce battle between Dodge City hunters and Indians, was a great range for buffalo; and perhaps a description of it, at that time, would be in order. A writer in a Texas paper, in 1881, treats the subject in an interesting way:

“There is something romantic about these canyons and surrounding plains, familiarly known as the ‘Llano Estacado.’ One would imagine a boundless stretch of prairie, limited, in all directions, by the horizon, a monotonous, dreary waste, the Great American Desert, offering but little to invite settlement or attract interest. My observation, from two months’ surveying and prospecting in this ‘terra incognita,’ has convinced me of the error of any previous opinions I may have formed of this section of the state. The canyons, hemmed in by the plains, the latter rising some two hundred feet above the bed of the streams in the former, are as fair and picturesque as the famous Valley of the Shenandoah, or the most favored sections, in this respect, in California, affording perennial springs of pure, sweet, and mineral waters, gypsum, salt, iron, lime, and sulphur; also, nutritious grasses, green all winter, capable of sustaining sufficient cattle to supply a nation.

“The breaks of the plains, corresponding to second valley prairie, incrusted with pure white gypsum and mica, assuming many dazzling shapes, remind one of the

-196-

battlements of an old fort or castle, or the profile of a large city with its cathedral walls and varied habitations of the humble and princely of a huge metropolis. Romance lingers on the. summit of these horizontal, fancifully shaped bluffs of the Llano Estacado, so called, and the dreamer or romancer would never exhaust his genius in painting vivid pictures of the imagination.

“This portion of the state, having little protection from the incursions of the Indians, has not yet been a favorite field for settlement, and only within the past three or four years a few hardy, fearless stockmen have brought out their flocks, from the overcrowded ranges of the interior, to enjoy the rich pasturage afforded here. These pioneers, for such they are and deserve to be regarded as stockmen, are. traduced and misrepresented, and live in the most primitive style imaginable. A cave in the grounds, in many instances, covered only with poles and earth, affords them shelter from the snow and blood-freezing northers, which come often with the force and intensity of a sirocco, from the timberless plains.

“Agriculture has not been tried here, but, the soil in this and many of the surrounding counties, a red chocolate loam, in some instances a mold, must yield abundantly to the efforts of the husbandman. The immense amount of snow (we have it on the ground now five inches deep), falling during the fall months, it seems would prepare the soil for early spring crops of cereals; and the volunteer plum thickets and currants indicate that many of the fruits would do well here. The rainfall, so I am informed by the settlers, has averaged well for many years past, even upon the plains; and, with the exception of a few arid sand wastes and salt deposits, it is fair to predict that, in time, the Great American Desert will have followed the red man, or proved as veritable a myth as the Wandering Jew.

-197-

“The tall sedge grass upon the plains has been burning for a week or more past, only ceasing with the recent snowfalls, and the canyons are lit up as by the intensity of a Syrian sun or electric light. These annual burnings are really an advantage, fertilizing and adding strength to the spring grasses.”

Notwithstanding the possibilities of the Llano Estacado and other sections of the great plains, one can imagine what the lives of the buffalo hunters must have been amid such wild and comfortless surroundings. For all that, many of the hunters seemed happy in the life, and occasionally one even waxed eloquent, not to say poetical, upon the subject. The following lines bear witness to this fact, being composed in the very midst of buffalo hunting days, by as unlikely an aspirant to efforts at poesy as one can well imagine. The lines are not classical, but, considering their author, they are as wonderful production of the pen as the perfect verses of scholarly Milton. Whatever their faults as literature, they at least give a concise and telling picture of the buffalo hunter’s life.

THE BUFFALO HUNTER

“Of all the lives beneath the sun,

The buffalo hunter’s is the jolliest one!

His wants are few, simple, and easily supplied,

A wagon, team, gun, and a horse to ride.

He chases the buffalo o’er the plains;

A shot at smaller game he disdains.

Bison hides are his bills of exchange.

And all are his that come within range;

From the wintry blast they shield his form,

And afford him shelter during the storm.

A steak from the hump is a feast for a king;

Brains, you know, are good, and tongue a delicious thing.

When the day’s hunt is over, and all have had their dinners,

-198-

The hunter lights his pipe, to entertain the skinners;

He tells of the big bull that bravely met his fate;

Of the splendid line shot that settled his mate;

Of the cow, shot too low, of another, too high;

And of all the shots that missed he tells the reason why;

How the spike stood his ground, when all but him had fled,

And refused to give it up till he filled him with lead;

How he trailed up the herd for five miles or more,

Leaving, over forty victims weltering in their gore;

All about the blasted calves that put the main herd to flight,

And kept them on the run until they disappeared from sight.

When weary of incidents relating to the chase,

They discuss other topics, each-one in its place;

Law, politics, religion, and the weather,

And the probable price of the buffalo leather.

A tender-footed hunter is a great greenhorn,

Ad the poor old granger an object of scorn;

But the worst deal of all is reserved for hide buyers,

Who are swindlers and robbers and professional liars.

The hunter thinks, sometimes in the future, of a change in his life,

And indulges in dreams of a home and a wife,

Who will sit by his side and listen to his story of the boys and the past,

And echo his hopes of reunion in the happy hunting grounds at last.”

My old friend and former partner, Charles Rath, was a great buffalo hunter and freighter. No one handled as many hides and robes as he, and few men killed more buffaloes. He was honest, true, and brave. He bought and sold more than a million of buffalo hides, and tens of thousands of buffalo robes, and hundreds of cars of buffalo meat, both dried and fresh, besides several carloads of buffalo tongues. He could speak the Cheyenne

-199-

and Arapahoe languages, and was one of the best sign men. He lived right among the Indians for many years and acquired their habits; but he never gained great confidence in them, and no man used greater precaution to guard against their attacks.

Nearly all of the buffalo hunters, bull-whackers, cowboys, and bad men had a popular nickname or peculiar title of some kind bestowed upon them, supposed to be more or less descriptive of some peculiarity in their make up, and which was often in such common use as to almost obscure the fact that the individual possessed any other or more conventional name. Prairie Dog Dave, Blue Pete, Mysterious Dave, and others are mentioned elsewhere in these pages. In addition, might be named, many others, some very significant and appropriate; such as, Dirty Face Charley, The Off Wheeler, The Near Wheeler, Eat ‘Em Up Jake, Shoot ‘Em Up Mike, Stink Finger Jim, The Hoo-Doo Kid, Frosty, The Whitey Kid, Light Fingered Jack, The Stuttering Kid, Dog Kelley, Black Kelley, Shot Gun Collins, Bull Whack Joe, Bar Keep Joe, Conch Jones, Black Warrior, Hurricane Bill, and Shoot His Eye Out Jack. Women were also often nicknamed, those of unsavory character generally taking a title of the same sort; and the married sharing the honors of their husbands title, as Hurricane Bill and Hurricane Minnie; Rowdy Joe and Rowdy Kate.

Prairie Dog Dave is distinguished as being the hunter who killed the famous white buffalo, which he sold to the writer for one thousand dollars, in the early days of Dodge City. So far as early settlers know, only one white buffalo has been known. Of the thousands upon thousands shot by the plainsmen, in buffalo hunting days, none were ever white. Naturally, Dave’s specimen, which I had mounted and shipped to Kansas City, forty years ago, attracted wide attention, not only in Kansas City, but throughout the West. It was exhibited at fairs and expositions, and Indians and plainsmen traveled for miles

-200-

to get a look at it. The specimen was loaned to the State of Kansas, and, until nine years ago, was on exhibition in the state capitol at Topeka.

I would feel that these sketches were incomplete did I not give at least a brief account of the “battle of the adobe wall,” in which the handful of brave men who fought so valiantly against the Indians were all Kansans.

Long years ago, before General Sam Houston led the Texans on to victory, before their independence was achieved, while the immense territory southwest of the Louisiana purchase was still the property of Mexico, a party of traders from Santa Fe wandered up into northwestern Texas and constructed a rude fort. Its walls, like those of many Mexican dwellings of the present day, were formed of a peculiar clay, hard baked by the sun. At that time the Indians of the plains were numerous and warlike, and white men who ventured far into their country found it necessary to be prepared to defend themselves in case of attacks. Doubtless the fortress served the purpose of its builders long and well. If the old adobe wall had been endowed with speech, what stories might it not have told of desperate warfare, of savage treachery, and the noble deeds of brave men. However, in the ’70’S, all that remained to even suggest these missing leaves of the early history of the plains were the outlines of the earthen fortifications.

In 1874 a number of buffalo hunters from Dodge City took up headquarters at the ruins. The place was selected, not only because of its location in the very center of the buffalo country, but also because of its numerous other advantages, and the proximity of a stream of crystal, clear water which flowed into the Canadian River a short distance below. After becoming settled at the trading post, and erecting two large houses of sod, which were used as store buildings, the men turned their attention to building a stockade, which

-201-

was never completed. As spring advanced and the weather became warm, the work lagged and the hunters became careless, frequently leaving the doors open at night to admit the free passage of air, and sleeping out-of-doors and late in the morning, until the sun was high.

Among the Indians of the plains was a medicine man, shrewd and watchful, who still cherished the hope that his people might eventually be able to overcome the white race and check the progress of civilization. After brooding over the matter for some time, he evolved a scheme, in which not only his own nation, but the Arapahoes, Comanches, and Apaches were interested. A federation was formed, and the Indians proceeded against the settlements of northwestern Texas and southwestern Kansas. Minimic, the medicine man, having observed that the old Mexican fort was again inhabited, and being fully informed with regard to the habits of the white men, led the warriors to attack the buffalo stations, promising them certain victory, without a battle. He had prepared his medicine carefully, and in consequence the doors of the houses would be open and the braves would enter in the early morning, while their victims were asleep, under the influence of his wonderful charm. They would kill and scalp every occupant of the place without danger to themselves, for his medicine was strong, and their war paint would render them invisible.

On the morning of the fight, some of the hunters who were going out that day were compelled to rise early. A man starting to the stream for water suddenly discovered the presence of Indians. He ran back and aroused his comrades; then rushed outside to awaken two men who were sleeping in wagons. Before this could be accomplished, the savages were swarming around them. The three men met a horrible death at the hands of the yelling and capering demons, who now surrounded the sod buildings. The roofs were covered with dirt, making it

-202-

impossible to set fire to them, and there were great double doors with heavy bars. There were loopholes in the building, through which those within could shoot at the enemy.

The Indians, sure of triumph, were unusually daring, and again and again they dashed up to the entrances, three abreast, then suddenly wheeling their horses, backed against the doors with all possible force. The pressure was counteracted by barricading with sacks of flour. The doors were pushed in by the weight of the horses, until there was a small crevice through which they would hurl their lances, shoot their arrows, and fire their guns as they dashed by. Now they would renew their attack more vigorously than ever, and dash up to the port holes by the hundreds, regardless of the hunters’ deadly aim. Saddle after saddle would be empty after each charge, and the loose horses rushed madly around, adding to the deadly strife and noise of battle going on. At one time there was a lull in the fight; there was a young warrior, more daring and desperate than his fellows, mounted on a magnificent pony, decorated with a gaudy war bonnet, and his other apparel equally as brilliant, who wanted, perhaps, to gain distinction for his bravery and become a great chief of his tribe, made a bold dash from among his comrades toward the buildings. He rode with the speed of an eagle, and as straight as an arrow, for the side of the building where the port holes were most numerous and danger greatest, succeeded in reaching them, and, leaping from his horse, pushed his six-shooter through a port hole and emptied it, filling the room with smoke. He then attempted a retreat, but in a moment he was shot down; he staggered to his feet, but was again shot down, and, whilst lying on the ground, he deliberately drew another pistol from his belt and blew out his brains.

There were only fourteen guns all told with the hunters, and certainly there were over five hundred

-203-

Indians, by their own admission afterwards. The ground around, after the fight, was strewn with dead horses and Indians. Twenty-seven of the latter lay dead, besides a number of them had been carried off by their comrades. How many wounded there were we never knew, and they (the Indians) would never tell, perhaps, because they were so chagrined at their terrible defeat. After the ammunition had been exhausted, some of the men melted lead and molded bullets, while the remainder kept up the firing, which continued throughout the entire day. Minimic rode from place to place with an air of braggadocio encouraging his followers and making himself generally conspicuous. A sharpshooter aimed at him, in the distance, possibly a mile, and succeeded in killing the gaily painted pony of the prophet. When the pony went down, Minimic explained to his followers that it was because the bullet had struck where there was no painted place. In the midst of the excitement, while bullets were flying thick and fast, a mortally wounded savage fell almost on the threshold of one of the stores. Billy Tyler, moved with pity, attempted to open the door in order to draw him inside, but was instantly killed. The struggle lasted until dark, when the Indians, defeated by fourteen brave men, fell back, with many dead and wounded. The hunters had lost four of their number, but within a few days two hundred men collected within the fortifications, and the allies did not venture to renew the conflict. Old settlers agree that the “battle of adobe wall” was one of the fiercest fought on the plains. Such is a brief account, founded on the author’s personal knowledge, of the “adobe wall fight,” in the Panhandle of Texas, just due south of Dodge, all who were engaged in it being formerly citizens of Dodge. In addition I herewith give the story of one of the participants:

“Just before sunrise on the morning of June 27th, 1874, we were attacked by some five hundred Indians. The walls were defended by only fourteen guns. There

-204-

were twenty-one whites at the walls, but the other seven were non-combatants and had no guns. It was a thrilling episode, more wonderful than any ever pictured in a dime novel, and has the advantage over the average Indian story in being true, as several of the leading men of Dodge City can testify, who were present at the fight, among them being Mr. W. B. Masterson, sheriff of our county.

“About three o’clock in the morning of the fight, several parties sleeping in the saloon of Mr. James Haner then were awakened by the falling in of part of the roof which had given way. The men awakened by the crash jumped up, thinking they had been attacked by Indians, but, discovering what was the matter, proceeded to make the necessary repairs. It was about daylight when through, and Billy Ogg went out to get the horses which were picketed a short distance from the house. He discovered the Indians, charging down from the hills, and immediately gave the alarm and started for the building. The Indians charged down upon the little garrison in solid mass, every man having time to get to shelter except the two Sheidler brothers and a Mexican bull-whacker, who were sleeping in their wagons a short distance from the walls, and who were killed and their bodies horribly mutilated. They were just about to start for Dodge City, loaded with hides for Charles Rath & Company.

“The red devils charged right down to the doors and port holes of the stockade, but were met with such a galling fire they were forced to retire. So close were they that, as the brave defenders of the wall shot out of their portholes, they planted the muzzles of their guns in the very faces and breasts of the savages, who rained a perfect storm of bullets down upon them. For two terrible hours did the Indians, who displayed a bravery and recklessness never before surpassed and seldom equalled, make successive charges upon the walls, each time being driven

-205-

back by the grim and determined men behind, who fired with a rapidity and decision which laid many a brave upon the ground. But two men were killed in the stockade, Billy Tyler, who was trying to draw in a wounded Indian, mortally wounded and lying groaning against the door, which, when Tyler opened it, he was shot. The Indian who gave Tyler his death wound was scarcely fifteen feet from him at the time. A man, by the name of aIds, was coming down the ladder from the lookout post, with his gun carelessly in front of him, and the hammer. caught on something, the ban entering his chin and coming out the top of his head.

“After two hours’ hard fighting, the Indians withdrew to the hills but kept up a bombardment on the stockade for some time afterwards. In the afternoon, while the bullets were coming down on them like hailstones, Masterson, Bermuda, and Andy Johnson came out and found ten Indians and a negro dead; but when the savages were driven in by General Miles, they acknowledged to seventy being killed, and God knows how many were wounded.

“The Comanches, in the adobe wall fight, were led by Big Bow; the Kiowas by Lone W 01Å“; and the Cheyennes by Minimic, Red Moon, and Gray Beard. The Indians, shortly afterwards, were completely subdued by that indefatigable Indian trailer and fighter, the gallant General Miles. The Miles expedition started from Dodge on the 6th of August, and on the 30th fought the redskins on Red River. Masterson, who participated in the adobe wall fight, went out with the expedition as a scout under Lieutenant Baldwin, of the gallant old Fifth Infantry, and was with Baldwin at the time of the capture of the Germain children.”

As an example of fighting of a different sort, I must here relate the story of a little fight between the Indians and hunters. Charles Rath & Company loaded a small mule train, belonging to the hunters, with ammunition

-206-

and guns for their hunters’ store at adobe walls. When about half way, on the old Jones and Plummer trail, they were suddenly rushed by a band of Indians five times their number. The hunters hastily ran their wagons into corral shape, and turned loose on them. The Indians were only too glad to skedaddle, leaving several dead horses behind. The hunters pulled into the trail and went on, without losing a moment’s time. The Indians killed a favorite buffalo pony, which was the only injury the hunters sustained, and they saw no more of Mr. Redskin.

While much of the history connected with the buffalo is nothing but a record of hardships, fighting, and slaughter of various sorts, there is a brighter tinge to it, now and then, and sometimes its incidents are even laughable, as the story of Harris’ ring performance with the bull buffalo, in another chapter, can testify. In many ways, the buffalo was much like domestic cattle in their nature. They could be tamed, handled, and trusted to the same extent. At one time, in Dodge City’s early days, Mr. Reynolds had two very tame, two-year-old buffaloes. They were so exceedingly tame and docile that they came right into the back yards, and poked their noses into the kitchen doors, for bread and other eatables.

There came a large troupe to Dodge City, to play a week’s engagement at our nice little opera house, just built. They had a big flashy band of about twenty-four pieces, their dress was very gaudy, indeed-like Jacob’s coat, made up of many colors-and their instruments, as well as their uniforms, were very brilliant; so much so that they attracted great attention, and I presume their flashy appearance also attracted the attention of the two tame buffaloes, who took exceptions to the noise and appearance, and they took their time and opportunity to resent it.

The band leader was a great tall man, and he had a big bear-skin cap, a baton, and all the shiny regalia they generally wear. Now, as this big bang was strung

-207-

out, coming down Bridge Street, playing for all that was out, those two buffaloes were listening in their back yard, and began to snort and show other signs of restlessness. The band leader stepped out of the ranks, shook his baton, and flourished it right in the buffaloes’ faces. This was too much-or more than the buffaloes could stand, and they made a vicious charge at the fellow. With heads lowered, they made for him, and of course he ran right into his band, the buffaloes following with nostrils distended and blood in their eyes. The waterworks had the street all torn up, a big ditch full of water in the middle of the street, and a picket fence on each side. On charged the buffaloes, homing and plunging into everything in sight. The big bass drum was thrown up into the air, and, as it came down, the buffaloes went for it, as well as for the members of the band, and such a scatterment you never saw. Some took the fence; some took the ditch; all threw away their instruments; some had the seats of their pants torn out; the drum major lost his big hat; and there were those who took the fence, roosting there on the pickets, holloing like good fellows to be rescued.

Now this might have been the last of it; but that night, when the buffalo charge had been forgotten, and the band was drawn up in the street, playing in front of the opera house before the performance, some mischievous persons led the two buffaloes down, and turned them loose in the rear of that band, with a big send off, driving them right into the thickets of the band. This was enough. They not only threw away their instruments, but took to their heels, shouting and holloing, almost paralyzed with fear.

-208-