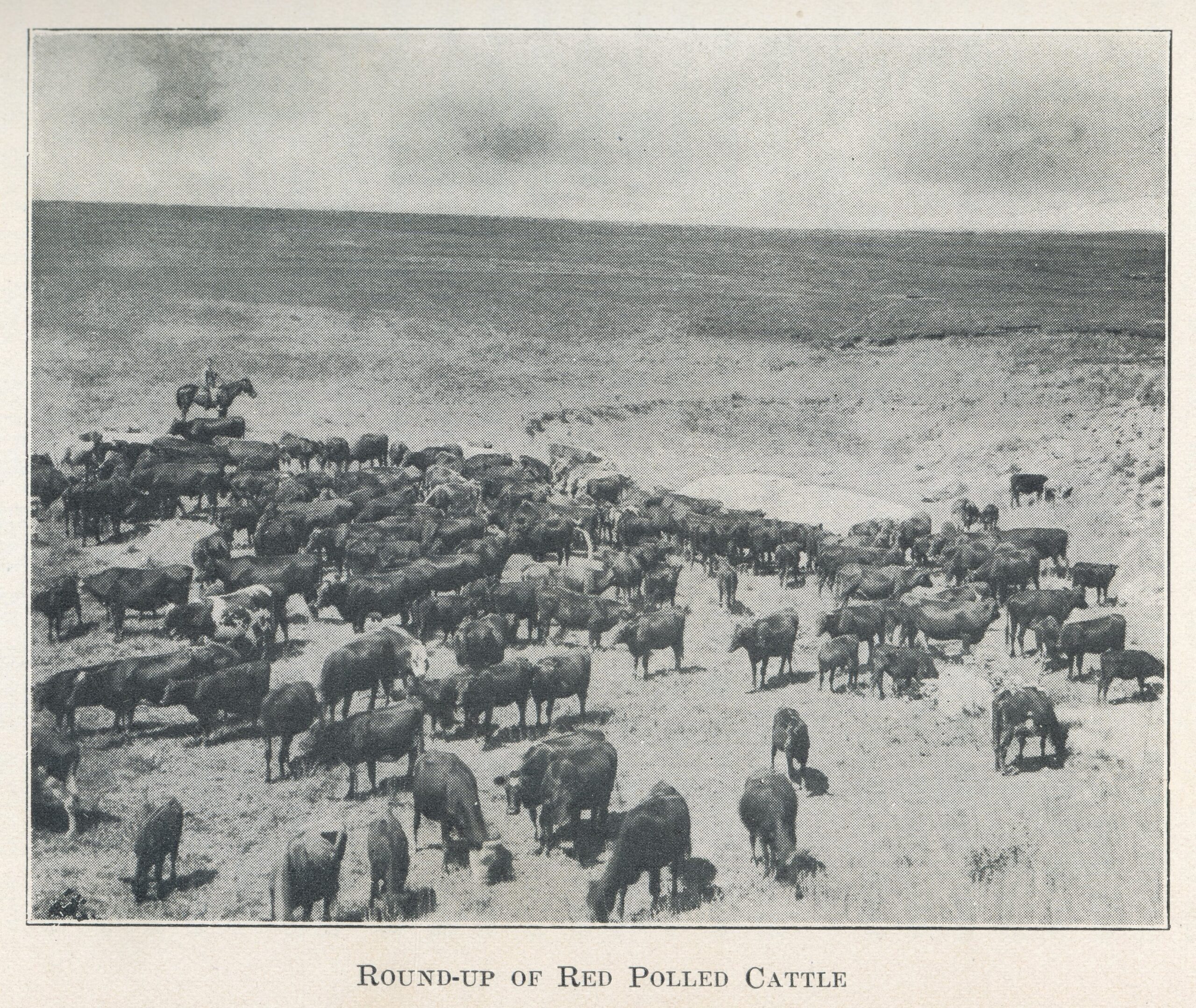

FOR a few of Dodge City’s earliest years, the great herds of buffalo were the source from which sprung a large share of the business activity and prosperity of the place. As has been virtually stated, buffalo hunting was a regular vocation, and traffic in buffalo hides and meat a business of vast proportions. But after a time, the source of this business began to fail, and something to take its place was necessary if a gap were not to be left in Dodge City’s industrial world. A substitute, in the form of a new industry, was not wanting, however, for immediately in the wake of the buffalo hunter came the cowboy, and following the buffalo came the long-horned steer. As the herds of the former receded and vanished, the herds of the latter advanced and multiplied, until countless numbers of buffaloes were wholly supplanted by countless numbers of cattle, and Dodge City was surrounded with new-fashioned herds in quite the old-fashioned way. Being the border railroad town, Dodge also became at once the cattle market for the whole southwestern frontier, and, very shortly, the cattle business became enormous, being practically all of that connected with western Kansas, eastern Colorado, New Mexico, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), and Texas. Cattle were driven to Dodge, at intervals, from all these points for sale and transportation, but the regular yearly drive from the ranges of Texas was so much greater in numbers and importance than the others, that they were quite obscured by it, while the Texas drive became famous for its immensity.

The “Kansas City Indicator,” and other relievable papers and estimates, place the drive north from Texas, from 1866 to 1878, at 3,413,513 head. The “San Antonio

-259-

Express” says of the enormous number: “Place a low average receipt of seven dollars per head, yet we have the great sum of $24,004,591.00. Not more than half of this vast amount of money finds its way back to the state, but much the larger portion is frittered away by the reckless owner and more reckless cowboy.” Of this money, a contemporary writer says: “Of course Dodge receives her portion which adds greatly to the prosperity of the town and helps build up our city. The buyers pay on an average of eight dollars per head for yearling steers and seven dollars for heifers. They place these yearling steers on ranches, both north and south of us, and market them in two years, when they net in Kansas City, Chicago, and other markets at twenty-five dollars, making the net profit of two hundred per cent on their investments or doubling their capital twice over, as their losses are not more than two or three per cent, and the cost of running them for two years are very light.”

They paid no taxes; they paid no rent for their ranches; al1 their ranges were free. The cost of living was very light, and all they were out were the men’s wages. You can readily see how all those engaged in the stock business quickly made fortunes, and the business was the cleanest, healthiest on earth.

The cattle drive to Dodge City first began in 1875-1876, when there were nearly two hundred and fifty thousand head driven to this point. In 1877, there were over three hundred thousand, and the number each year continued to increase until the drive reached nearly a half million. We held the trade for ten years, until 1886, when the dead line was moved to the state line. There were more cattle driven to Dodge, any and every year that Dodge held it, than to any other town in the state, and Dodge held it three times longer than any other town, and, for about ten years, Dodge was the greatest cattle market in the world. Yes, all the towns that enjoyed the

-260-

trade of the Texas Drive, Dodge exceeded greatly in number, and held it much longer. In corroboration of this assertion, I give a quotation from the “Kansas City Times,” of that period, thus:

“Dodge City has become the great bovine market of the world, the number of buyers from afar being unprecedently large this year, giving an impetus to the cattle trade that cannot but speedily show its fruits. The wonderfully rank growth of grasses and an abundance of water this season has brought the condition of the stock to the very highest standard, the ruling prices showing a corresponding improvement. There are now upwards of one hundred thousand head of cattle in the immediate vicinity of Dodge City, and some of the herds run high into the thousands. There is a single herd numbering forty thousand, another of seventeen thousand, another of twenty-one thousand, and several of five thousand or thereabouts. On Saturday, no less than twenty-five thousand were sold. The Texas drive to Dodge this year will run close to two hundred thousand head.”

A “Kansas City Times” correspondent, in a letter headed, “Dodge City, Kansas, May 28th, 1877,” writes up the subject as follows:

“Abilene, Ellsworth, and Hays City on the Kansas Pacific railroad, then Newton and Wichita, and now Dodge City on the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe road, have all, in their turn, enjoyed the ‘boil and bubble, toil trouble’ of the Texas cattle trade.

“Three hundred and sixty-seven miles west from Kansas City we step off at Dodge, slumbering as yet (8:30 a.m.) in the tranquil stillness of a May morning. In this respect Dodge is peculiar. She awakes from her slumbers about eleven, a. m., takes her sugar and lemon at twelve m., a square meal at one p. m., commences biz

-261-

at two o’clock, gets lively at four, and at ten it is hip-hip hurrah! till five in the morning.

“Not being a full-fledged Dodgeite, we breakfasted with Deacon Cox, of the Dodge House, at nine o’clock, and meandered around until we found ourselves on top of the new and handsome courthouse. A lovely prairie landscape was here spread out before us. Five miles to the southeast nestled Fort Dodge, coyly hiding, one would think, in the brawny arm of the Arkansas. Then, as far as the eye could reach, for miles up the river and past the city, the bright green velvety carpet was dotted by thousands of long-horns which have, in the last few days, arrived, after months of travel, some of them from beyond the Rio Grande and which may, in a few more months, give the Bashi Bazouks fresh courage for chopping up the Christians and carrying out the dictates of their Koran. But we are too far off. We have invaded Turkey with Texas beef, and, though a long-horned subject must be somewhat contracted here.

” Dodge City has now about twelve hundred inhabitants-residents we mean, for there is a daily population of twice that many; six or seven large general stores, the largest of which, Rath & Wright, does a quarter of a million retail trade in a year; and the usual complement of drug stores, bakers, butchers, blacksmiths, etc.; and last, but not by any means the least, nineteen saloons no little ten-by-twelves, but seventy-five to one hundred feet long, glittering with paint and mirrors, and some of them paying one hundred dollars per month rent for the naked room.

“Dodge, we find, is in the track of the San Juanist, numbers of which stop here to outfit, on their way to the silvery hills.

“We had the good luck to interview Judge Beverly of Texas, who is the acknowledged oracle of the cattle trade. He estimates the drive at two hundred and eighty

-262-

five thousand, probably amounting to three hundred thousand, including calves. Three-quarters of all will probably stop at Dodge and be manipulated over the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, by that prince of railroad agents, J. H. Phillips, Esq. Herbert, as he is familiarly called, is a graduate of Tammany Hall and is understood to wear in his shirt front the identical solitaire once worn by Boss Tweed. It is hinted that Herbert will buy every hoof destined for the Kansas Pacific road, at four times its value, rather than see them go that way. He would long, long ago have been a white-winged angel, playing on the harp of a thousand strings, were it not for the baneful associations of Frazer, Sheedy, Cook, et al. You can hear more about ‘cutting out,’ ’rounding up,’ etc., in Dodge, in fifteen minutes, than you can hear in small towns like Chicago and St. Louis in a lifetime.”

In the same year, another newspaper representative, G. C. Noble, who visited Dodge, describes his impressions as follows:

“At Dodge City we found everything and everybody busy as they could comfortably be. This being my first visit to the metropolis of the West, we were very pleasantly surprised, after the cock and bull stories that lunatic correspondents had given the public. Not a man was swinging from a telegraph pole; not a pistol was fired; no disturbance of any kind was noted. Instead of being called on to disgorge the few ducats in our possession, we were hospitably treated by all. It might be unpleasant for one or two old time correspondents to be seen here, but they deserve all that would be meted out to them. The Texas cattlemen and cowboys, instead of being armed to the teeth, with blood in their eye, conduct themselves with propriety, many of them being thorough gentlemen.

“Dodge City is supported principally by the immense cattle trade that is carried on here. During the season that has just now fairly opened, not less than two

-263-

hundred thousand head will find a market here, and there are nearly a hundred purchasers who make their headquarters here during the season. Mr. A. H. Johnson, the gentlemanly stock agent of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Company, informs us that the drive to this point, during the season, will be larger than ever before.

“From our window in the Dodge House, which by the way, is one of the best and most commodious in the west, can be seen five herds, ranging from one thousand to ten thousand each, that are awaiting transportation. The stock yards here are the largest west of St. Louis, and just now are well filled.

“Charles Rath & Company have a yard in which are about fifty thousand green and dried buffalo hides.

“F.C. Zimmerman, an old patron of the ‘Champion,’ runs a general outfitting store, and flourishes financially and physically. Many other friends of the leading journal are doing business, and are awaiting patiently the opening up of the country to agricultural purposes.

“In the long run, Dodge is destined to become the metropolis of western Kansas and only awaits the development of its vast resources.

One more brief extract from a visitor’s account of his visit “among the long-horns”, and the extent and importance of Dodge City’s early cattle trade will have been sufficiently established to permit my proceeding to some of the peculiar phases of that trade and the life of the stockmen and cowboys. This visitor sees the facetious side of the Dodge cattle traffic:

“This is May, 1877, Dodge City boiling over with buyers and drivers. ‘Dodge City!’ called the brakeman, and, with about thirty other sinners, we strung out to the Dodge House to command the register with our autographs, deposit our grip-sacks with Deacon Cox, and breakfast. But what a crowd is this we have elbowed

-264-

our reportorial nose into? and bless your soul, what a sight! It just looks like all Texas was here. We now learn that everybody not at the Dodge House is at the Alamo. The Alamo is presided over by a reformed Quaker from New York, and it is hinted that the manner in which he concocts a toddy (every genuine cattleman drinks toddy) increases the value of a Texas steer two dollars and seventy-five cents. There is about seventy-five thousand head around town. Everybody is buying and selling. Everything you hear is about beeves and steers and cows and toddies and cocktails. The grass is remarkably fine; the water is plenty; two drinks for a quarter, and no grangers. These facts make Dodge City the cattle point.”

Notwithstanding the regularity of the great drives into Dodge, their magnitude, and the general popularity of the cattle trade as a business, the life of the cowboys and drovers was, by no means, an easy one. It was beset on every hand by hardship and danger. Exposure and privation continually tried the man who was out with the great herds; accidents, stampedes, and other dangers continually harassed him with fears for the safety of his mounts and his charge.

A little item which appeared in the “Dodge City Times”, of April 6th, 1878, read like this: “Mr. Jesse Evans and his outfit, consisting of fifty men and five four-mule teams and a number of saddle horses, started for the southwest yesterday. They go to New Mexico to gather from the ranges about twenty thousand cattle that Mr. Evans has purchased and will bring to Dodge City for sale and shipment.” This expedition appeared simple and easy enough, from the tone of the item, but it gave no idea at all of the real facts in the case.

the fifty men were picked up in Dodge City. They were all fighters and gun-men, selected because they were such, for, in gathering these twenty thousand head of

-265-

cattle, they did so from under the very noses of the worst set of stock thieves and outlaws ever banded together, who were the Pecos River gang, with the famous “Billy the Kid” as leader. But they took the cattle without much fighting, and delivered them safely at Jesse Evan’s ranch just southeast of Dodge.

These men suffered incredible hardships on the drive up. Before they were halfway back, winter overtook them, and their horses necessarily being thin from the terrible work they had done, could not survive the cold storms, but lay down and died. There was scarcely a mount left. The men were all afoot, and barefooted at that, and had to often help draw the mess wagon by hand. They lived for weeks on nothing but fresh beef, often without salt; no sugar, no coffee, no flour, no nothing, but beef, beef, all the time, and they were the most woe begone, ragged, long-haired outfit I ever saw-scarcely any clothing except old blankets tied around them in every fashion; no shoes or hats; indeed, they were almost naked. But I tell you what they did have a plenty; it was “gray-backs”. With their long hair and long beards, these little “varmints” were having a feast, and the men bragged about these little pests keeping them alive and warm, for, in scratching so much, it gave good circulation to their blood. But notwithstanding their long hair and naked, dirty, lousy bodies, the men were in splendid health. They wandered into Dodge, one and two at a time, and, in this manner, it was two days and nights before they all straggled in.

Perhaps the most dangerous, most dreaded, and most carefully guarded against phase of cattle driving was the stampede, where all the skill, nerve, and endurance of the drivers were tested to the limit. A common dark lantern was often a feature at such times. The part it played in quelling and controlling a stampede, as well as some feature of the stampede itself, is well described, by a writer of cattle driving days, in this wise:

-266-

“One of the greatest aids to the cowboys during a stampede, on a dark stormy night, is the bull’s-eye lantern, and it so simple and handy. We all know when a stampede starts it is generally on a dark, stormy night. The cowboy jumps up, seizes his horse, and starts with a bound to follow the noise of the retreating herd, well knowing, as he does, the great danger before him; oftentimes encountering a steep bank, ten to twenty and sometimes thirty feet high, over which his horse plunges at full speed, to their certain death. For he knows not where the cattle, crazed by fear, will take him, but he does know it is his duty to follow as close as the speed of his horse will take him. This friend of his, the bull’s-eye lantern, was discovered by accident. The flash of the lantern, thrown upon the bewildered herd, restores it to its equilibrium, and, in its second affright, produces a reaction, as it were, and, being completely subdued, the stampede is stopped, during the most tempestuous raging of the elements. The old-fashioned way was to ride to the front of the herd and fire their guns in the faces of the cattle. Now, they throw the flash of the lantern across the front of the herd and flash the bull’s-eye into their faces, which is much more effective. The courage of the cowboy is demonstrated frequently on the long trail, but few of the cowboys are unequal to the emergencies.”

As a result of the widespread stealing of cattle and horses, especially horses, which went on in connection with the great cattle traffic, the papers of the day abounded with notices like the following from the “Dodge City Times”, of March 30th, 1878.

“Mr. H. Spangler, of Lake City, Comanche County, arrived in the city last Saturday in search of two horses that had been stolen from him last December. He described the stolen stock to Sheriff Masterson who immediately instituted search. On Monday he found one of the

-267-

horses, a very valuable animal, at Mueller’s cattle ranch on the Saw Log, it having been traded to Mr. Wolf. The horse was turned over to the owner. The sheriff has trace of the other horse and will endeavor to recover it.”

Many were the stories, of many different sorts, told about stock stealing and stock thieves. Some of these even took a humorous turn. One such, as told in early days, though funny was, nevertheless, true, and some do say that the man only took back what was taken from him, and it was (honestly or dishonestly) his horse. The reader may form his own opinion after perusing the story, as follows:

“Mr. O’Brien arrived in Dodge City last Sunday, August 30th, 1877, with the property, leaving, as we stated, our hero on the open prairie.

“We can picture in our minds this festive horse-thief, as he wandered over this sandy plain, under the burning sun, bereft of the things he holds most dear, to-wit: his horse, his saddle, and his gun. His feet became sore, his lips parched, and he feels, verily, he is not in luck. At last he can hold his pent-up passion no longer. A pale gray look comes into his face, and a steel gray look into his eye, and he swears by the great god of all horse-thieves (Dutch Henry) that he will show his oppressors a trick or two-that he will show them an aggrieved knight of the saddle knows no fear. His resolve is to recapture his horse or die in the attempt. A most noble resolve. The horse is his own by all laws known to horse-thieves in every land. It is his because he stole it. Now, be it known that this particular horse was a good horse, a horse whose speed was fast and whose wind was good, so to speak. This horse he loved because he was a fast horse and no common plug could run with half as much speed. Seated in the saddle on the back of this noble animal, our hero feared not even the lightning in its rapid career. As we said before, his determination was fixed

-268-

and his eye was sot. He would recapture the noble beast or he would die in the attempt. It was a go on foot and alone. He struck out. At the first hunters’ camp he stole a gun, a pair of boots, and a sack of flour. He stole these articles because he had to have them, and it was a ground-hog case. On he came toward our beautiful city .His knowledge of the. country led him direct to the farm of a rich farmer. As he approached he primed his gun, dropped lightly on hands and knees, and, with the demon glowing in his eye, stole silently through the tall buffalo grass to the house. Just at this time Mr. O’Brien happened to be riding out from town.. He was riding directly by the place where our hero was concealed, and his first intimation of the presence of anyone was the sight of the man he met the Sunday before, with his gun cocked and pointed at him. ‘Throw up your hands,’ said the horsethief; you have a small pistol in your belt-throw that down.’ Mr. O’Brien obeyed. ‘Now march to the stable before me, get my saddle and gun, and curry and saddle my horse which is picketed yonder, and await further orders.’

“Now, it so happened that the wealthy farmer was walking out that evening with his shotgun on his arm. He came to the stable, but, just as he turned the corner, the muzzle of a gun was placed near his head, and the word, ‘Halt!’ uttered. The rich farmer said, ‘What do you want?’ ‘My horse, saddle, and bridle.’ ‘What else?’ ‘Nothing.’. The farmer made a move as if he would use his gun. The horse-thief said, ‘Do not move or you will be hurt.’ Silence for a moment, then, ‘Lay down your gun.’ The gun was laid down. By this time, Mr. O’Brien came out with the saddle and gun, the gun being strapped in the scabbard. Keeping them both under cover of his rifle, the horse-thief ordered them to walk before him to his horse and ordered Mr. O’Brien to saddle and bridle the horse, which he did. Our hero then mounted his brave steed and told his reluctant companions that if they pur-

-269-

sued him their lives would be worthless, and then he sped off like the wind.” Reader, “such is life in the far west.”

Besides stock thieves and stealing, the cattle trade of early Dodge was attended by many other desperate characters and irregular practices, that were long in being stamped out. No better way of describing these desperate characters and irregular practices is at hand than by introducing a few specimens, for the reader’s consideration.

Two of the greatest gamblers and faro-bank fiends, as well as two of the most desperate men and sure shots, were Ben and Billy Thompson. Every year, without fail, they came to Dodge to meet the Texas drive. Each brothers had killed several men, and they were both dead shots. They terrorized Ellsworth county and city, the first year of the drive to that place, killed the sheriff of the county, a brave and fearless officer, together with several deputies, defied the sheriff’s posse, and made their “get away”.

A large reward was offered for them and they were pursued all over the country; but, having many friends among the big, rich cattlemen, they finally gave themselves up and, through the influence of these men who expended large sums of money in their defense, they were cleared. Ben told the writer that he never carried but one gun. He never missed, and always shot his victim through the head. He said, when he shot a man, he looked the crowd over carefully, and if the man had any close friends around or any dangerous witness was around, he would down him to destroy evidence. The last few years of his life, he never went to bed without a full quart bottle of three-star Hennessey brandy, and he always emptied the bottle before daylight. He could not sleep without it.

Ben was a great favorite with the stockmen. They needed him in their business for, be it said to their shame, some of them employed killers to protect their stock and

-270-

ranges and other privileges, and Ben could get any reasonable sum, from one hundred to several thousand dollars, with which to deal or play bank.

Ben Thompson was the boss among the gamblers and killers at Austin, and a man whose name I have forgotten, Bishop, I think, a man of wealth and property, who owned saloons and dance halls and theaters at San Antonio, was the boss of the killers of that town. Great rivalry existed between these two men, and they were determined to kill each other. Word was brought to the San Antonio gent that Ben was coming down to kill him, so he had fair warning and made preparations. Ben arrived in town and walked in front of his saloon. He knew Ben was looking for the drop on him and would be sure to come back the same way, so he stationed himself behind his screen in front of his door, with a double-barreled shotgun. Whether Ben was wise to this, I do not know, but when Ben came back, he fired through this screen, and the San, Antonio man fell dead with a bullet hole in his head, and both barrels of his gun were discharged into the floor.

Ben was now surely the boss, and numerous friends flocked to his standard, for “nothing succeeds like success”. Some say that this victory made Ben too reckless and fool-hardy, however.

Some time after this, the cattlemen gathered in Austin at a big convention. At this convention, Ben was more dissipated and reckless than ever, and cut a big figure. There was a congressman who resided at Austin, who was Ben’s lawyer and friend (I won’t mention his name). After the convention adjourned, thirty or forty of the principal stockmen and residents of Texas remained to close up business and give a grand banquet (and let me say right here, these men were no cowards). That night, Ben learned that they had not invited his congressman, to which slight he took exceptions. The

-271-

plates were all laid, wine at each plate, and just as they were about to be seated, in marched Ben with a six-shooter in his hand. He began at one end of the long table and smashed the bottles of wine, and chinaware as he came to it, making a clean sweep the ,entire length of the table. Let me tell you, before he got half through with his smashing process, that banquet hall was deserted. Some rushed through the doors, some took their exit through the windows, and in some instances the sash of the windows went with them and they did not stop to deprive themselves of it until they were out of range.

This exploit sounded Ben’s death knell, as I remarked at the time that it would, because I knew these men.

Major Seth Mabrey was asked, the next day, what he thought of Ben’s performance. Mabrey had a little twang in his speech and talked a little through his nose. In his slow and deliberate way, he said: “By Ginneys! I always thought, until last night, that Ben Thompson was a brave man, but I have changed my mind. If he had been a brave man, he would have attacked the whole convention when we were together and three thousand strong, but instead, he let nearly all of them get out of town, and cut off a little bunch of only about forty of us, and jumped ‘onto us.”

After this, the plans were laid to get away with Ben. He was invited to visit San Antonio and have one of the good old-time jamborees, and they would make it a rich treat for him. He accepted. They gave a big show at the theater for his especial benefit. When the “ball” was at its height, he was invited to the bar to take a drink, and, at a given signal, a dozen guns were turned loose on him. They say that some who were at the bar with him and who enticed him there were killed with him, as they had to shoot through them to reach Ben. At any rate, Ben never knew what hit him, he was shot up so badly. They were determined to make a good job of

-272-

it, for if they did not, they knew the consequences. Major Mabrey was indeed a cool deliberate, and brave man, but he admitted to outrunning the swiftest of them.

Major Mabrey would hire more than a hundred men every spring, for the drive, and it is said of him, that he never hired a man himself and looked him over carefully and had him sign a contract, that in months after he could not call him by name and tell when and where he had hired him.

The Major built the first castle or palatial residence on top of the big bluff overlooking the railroad yards and the Missouri River, in Kansas City, about where Keeley’s Institute now stands.

One of the most remarkable characters that ever came up the trail, and one whom I am going to give more than a passing notice, on account of his most remarkable career, is Ben Hodges, the horse-thief and outlaw.

A Mexican, or rather, a half-breed–half negro and half Mexican–came up with the first herds of cattle that made their way to Dodge. He was small of stature, wiry, and so very black that he was christened, “Nigger Ben.” His age was non-come-at-able. Sometimes he looked young, not over twenty or twenty-five; then, again, he would appear to be at least sixty, and, at the writing of this narrative, he is just the same, anq still resides in Dodge City.

Ben got stranded in Dodge City and was minus friends and money, and here he had to stay. At about the time he anchored in Dodge City, there was great excitement over the report that an old Spanish grant was still in existence, and that the claim was a valid one and embraced a greater part of the “Prairie Cattle Company’s” range.

While the stock men were discussing this, sitting on a bench in front of my store (Wright, Beverly & Company) Nigger Ben came along. Just as a joke, one of

-273-

them said: “Ben, you are a descendent of these old Spanish families; why don’t you put in a claim as heir to this grant?” Ben cocked up his ears and listened, took the cue at once, and went after it. As a novice, he succeeded in a way beyond all expectations. By degrees, he worked himself into the confidence of newcomers by telling them a pathetic story, and so, by slow degrees, he built upon his story, a little at a time, until it seemed to a stranger that Ben really did have some sort of a claim on this big grant, and, like a snowball, it continually grew. He impressed a bright lawyer with the truthfulness of his story, and this lawyer carefully prepared his papers to lay claim to the grant, and it began to look bright. Then Judge Sterry of Emporia, Kan., took the matter up! and not only gave it his time but furnished money to prosecute it. Of course, it was a good many years before his claim received recognition, as it had to be heard in one of our highest courts. But, in course of time, years after he began the action, it came to an end, as all things must, and the court got down ,to an investigation and consideration of the facts. It did not last but a moment, and was thrown out of court. Not the least shadow of a claim had Ben, but it was surprising how an ignorant darkey could make such a stir out of nothing.

Now, while this litigation was going on, Nigger Ben was not idle, for he started lots of big schemes and deals. For instance, he claimed to own thirty-two sections of land in Gray county, Kansas. About the time the United States Land Office was moved from Lamed to Garden City, Kansas, the Wright-Beverly store at Dodge burned, and their large safe tumbled into the debris in the basement, but the safe was a good one and nothing whatever in it was destroyed by the fire. This safe was used by the Texas drovers as a place in which to keep their money and valuable papers. Ben knew this, and, when the government land office was established at Garden City,

-274-

Ben wrote the officials and warned them not to take any filings on the thirty-two sections of land in Gray county, minutely describing the land by quarter sections. He told them that cowboys had filed on and proved up all these tracts and sold them to him, and that he had placed all the papers pertaining to the transactions in Wright, Beverly & Company’s safe, and that the papers were all destroyed by the fire. Now, to verify this, he had written to the treasurer of Gray County to make him a tax list of all these lands, which he did, and Ben would show these papers to the “tenderfeet” and tell them he owned all this land, and instanter attached them as supporters and friends, for no man could believe that even Ben could be such a monumental liar, and they thought that there must surely be some truth in his story.

He went to the president of the Dodge City National Bank, who was a newcomer, showed him the letter he received from the treasurer of Gray County, with a statement of the amount of tax on each tract of land, and, as a matter of course, this bank official supposed that he owned the land, and upon Ben’s request, he wrote him a letter of credit, reciting that he (Ben) was said to be the owner of thirty-two sections of good Kansas land and supposed to be the owner of a large Mexican land grant in New Mexico, on which were gold and silver mines, and quite a large town. He then went to the presidents of the other Dodge City banks and, by some means, strange to say, he got nearly as strong endorsements. As a joke, it is here related that these letters stated that Ben was sober and industrious, that he neither drank nor smoked; further, he was very economical, his expenses very light, that he was careful, that he never signed any notes or bonds, and never asked for like accommodations.

On the strength of these endorsements and letters, he bargained for thousands of cattle, and several herds were delivered at Henrietta and other points. Cattle advanced

-275-

in price materially that spring, and the owners were glad that Ben could not comply with his contracts to take them.

Quite a correspondence was opened by eastern capitalists and Omaha bankers with Ben, with a view to making him large loans of money, and, in the course of the negotiations, his letters were referred to me, as well as the Dodge City banks and other prominent business men for reports, here.

It is astounding and surprising what a swath Ben cut in commercial and financial circles. Besides, he successfully managed, each and every year, to get passes and annual free transportation from the large railroad systems. How he did it is a mystery to me, but he did it. If he failed with one official, he would try another, representing that he had large shipments of cattle to make from Texas and New Mexico, Indian Territory, and Colorado. He could just print his name, and he got an annual over the Fort Worth & Denver, and the writing of his name in the pass did not look good enough to Ben, so he erased it and printed his name in his own way. This was fatal; the first conductor took up his pass and put him off the train at Amarillo, Texas, and Ben had to beat his way back to Dodge City.

John Lytle and Major Conklin made a big drive, one spring, of between thirty and forty herds. They were unfortunate in encountering storms, and on the way, a great many of their horses and cattle were scattered. Each herd had its road brand. Mr. Lytle was north, attending to the delivery of the stock; Major Conklin was in Kansas City, attending to the firm’s business there; and Martin Culver was at Dodge City, passing on the cattle when they crossed the Arkansas River. Mr. Culver offered to pay one dollar per head for their cattle that were picked up, and two dollars per head for horses; and he would issue receipts for same which served as an order for the money on Major Conklin. Ben Hodges

-276-

knew all this and was familiar with their system of transacting business. Ben managed to get to Kansas City on a stock train, with receipts for several hundred cattle and a great many horses, supposed to be signed by Culver. (They were forgeries, of course). The receipts were for stock on the firm’s different road brands, and Major Conklin was astonished when he saw them. He did not know Ben very well and thought he would speculate a little and offered payment at a reduced price from that agreed upon. He asked Ben what he could do for him to relieve his immediate necessities, and Ben got a new suit of clothes, or, rather, a complete outfit from head to foot, ten dollars in money, and his. board paid for a week. In a few days Ben called for another ten dollars and another week’s board, and these demands continued for a month. Ben kept posted, and came to Conklin one day in a great hurry and told him that he must start for Dodge City at once, on pressing business, and that he was losing a great deal of money staying in Kansas City, and should be on the range picking up strays. The Major told Ben that Mr. Lytle would be home in a few days and he wanted Lytle to make final settlement with him (Ben). This was what Ben was trying to avoid. John Lytle was the last person in the world that Ben wanted to see. He told Conklin this was impossible, that he must go at once, and got twenty dollars and transportation to Dodge City from Conkling.

A few days afterwards, Lytle returned to Kansas City, and, in a crowd of stock men, at the St. James Hotel, that were sitting around taking ice in theirs every half hour and having a good time, Major Conklin very proudly produced his bunch of receipts he had procured from Ben in the way of compromise, as above related, and said: “John, I made a shrewd business deal and got your receipts for several hundred cattle and horses for less than half price, from Ben Hodges.” Enough had been said. All the cattlemen knew Ben, and both the

-277-

laugh and the drinks were on Conklin. He never heard the last of it and many times afterwards had to “set up” the drinks for taking advantage of an ignorant darkey. He was completely taken in himself.

One time Ben was in a hot box. It did look bad and gloomy for him. The writer did think truly and honestly that he was innocent, but the circumstantial evidence was so strong against him, he could hardly escape. I thought it was prejudice and ill feeling towards Ben, and nothing else, that induced them to bring the suit; and, what was worse for Ben, his reputation as a cattle thief and liar was very bad.

Mr. Cady had quite a large dairy, and one morning he awoke and found his entire herd of milch cows gone. They could get no trace of them, and, after hunting high and low, they jumped Ben and, little by little, they wove a network of circumstantial evidence around him that sure looked like they would convict him of the theft beyond a doubt. The district court was in session, Ben was arrested, and I, thinking the darkey innocent, went on his bond. Indeed, my sympathies went out to him, as he had no friends and no money, and I set about his discharge under my firm belief of his innocence.

I invited the judge down to my ranch at the fort to spend the night. He was a good friend of mine, but I hardly dared to advise him, but I thought I would throw a good dinner into the judge and, under the influence of a good cigar and a bottle of fine old wine, he would soften, and, in talking over old times, I would introduce the subject. I said, “Judge, I know you are an honest, fair man and want to see justice done; and you would hate to see an innocent, poor darkey, without any money or friends, sent to the pen for a crime he never committed.” And then I told him why I thought Ben was innocent. He said, “1 will have the very best lawyer at the bar take his case.” I said, “No, this is not at all what I want; I want Ben to plead his own case.” So I

-278-

gave Ben a few pointers, and I knew after he got through pleading before that jury, they would either take him for a knave or a fool.

I was not mistaken in my prophecy. Ben harangued that jury with such a conglomeration of absurdities and lies and outrageous tales, they did not know what to think. I tell you, they were all at sea. He said to them:

“What! me? the descendent of old grandees of Spain, the owner of a land grant in New Mexico embracing millions of acres, the owner of gold mines and villages and towns situated on that grant of whom I am sole owner, to steal a miserable, miserly lot of old cows? Why, the idea is absurd. No, gentlemen; I think too much of the race of men from which I sprang, to disgrace their memory. No, sir! no, sir! this Mexican would never be guilty of such. The reason they accuse me is because they are beneath me and jealous of me. They can’t trot in my class, because they are not fit for me to associate with and, therefore, they are mad at me and take this means . “to spite means to spite me.

Then he would take another tack and say: “I’se a poor, honest Mexican, ain’t got a dollar, and why do they want to grind me down? Because dey know 1 am way above them by birth and standing, and dey feel sore over it.” And then he would go off on the wildest tangent you ever listened to.

You could make nothing whatever out of it, and you’d rack your brains in trying to find out what he was trying to get at; and you would think he had completely wound himself up and would have to stop, but not he. \ He had set his mouth going and it wouldn’t stop yet, and,

in this way, did he amuse that jury for over two hours.

Sometimes he would have the jury laughing until the judge would have to stop them, and again, he would have the jury in deep thought. They were only out a little while, when they brought in a verdict of not guilty.

-279-

Strange to say, a few days afterwards that whole herd of milch cows came wandering back home, none the worse for their trip. You see, Ben had stolen the cattle, drove them north fifty or sixty miles, and hid them in a deep canyon or arroya. He had to leave them after his arrest and there came up a big storm, from the north, which drove the cattle home. I was much surprised when the cattle came back, for I knew, then, what had happened and that he was guilty.

I could fill a large book with events in the life of this remarkable fellow, but want of space compels me to close this narration here.

The life of the cowboy, the most distinguished denizen of the plains, was unique. The ordinary cowboy, with clanking spurs and huge sombrero, was a hardened case, in many particulars, but he had a generous nature. Allen McCandless gives the character and life of the cowboy in, “The Cowboy’s Soliloquy,” in verse, as follows:

“All o’er the prairies alone I ride,

Not e’en a dog to run by my side;

My fire I kindle with chips gathered round(*),

And boil my coffee without being ground.

Bread, lacking leaven, I bake in a pot,

And sleep on the ground, for want of a cot.

I wash in a puddle, and wipe on a sack,

And carry my wardrobe all on my back.

My ceiling’s the sky, my carpet the grass,

My music the lowing of herds as they pass;

My books are the brooks, my sermons the stones,

My parson a wolf on a pulpit of bones.

But then, if my cooking ain’t very complete,

Hygienists can’t blame me for living to eat;

And where is the man who sleeps more profound

Than the cowboy, who stretches himself on the ground.

My books teach me constancy ever to prize;

My sermons that small things I should not despise;

And my parson remarks, from his pulpit of bone,

-280-

That, ‘The Lord favors them who look out for their own.’

Between love and me, lies a gulf very wide,

And a luckier fellow may call her his bride;

But Cupid is always a friend to the bold,

And the best of his arrows are pointed with gold.

Friends gently hint I am going to grief;

But men must make money and women have beef.

Society bans me a savage, from Dodge;

And Masons would ball me out of their lodge.

If I’d hair on my chin, I might pass for the goat

That bore all the sin in the ages remote;

But why this is thusly, I don’t understand,

For each of the patriarchs owned a big brand.

Abraham emigrated in search of a range,

When water got scarce and he wanted a change;

Isaac had cattle in charge of Esau;

And Jacob ‘run cows’ for his father-in-law.

He started business clear down at bed-rock,

And made quite a fortune, watering stock;

David went from night herding, and using a sling,

To winning a battle and being a king;

And the shepherds, when watching their flocks on the hill,

Heard the message from heaven, of peace and good will.”

(*) “Chips” were dried droppings of the cattle. Buffalo “chips” were used as fuel by the plainsmen. .

Another description of the cowboy, different in character from the last, but no less true to life, is from an exchange, in 1883.

“The genuine cowboy is worth describing. In many respects, he is a wonderful creature. He endures hardships that would take the lives of most men, and is, therefore, a perfect type of physical manhood. He is the finest horseman in the world, and excells in all the rude sports of the field. He aims to be a dead shot, and universally is. Constantly, during the herding season, he rides seventy miles a day, and most of the year sleeps in the open

-281-

air. His life in the saddle makes him worship his horse, and it, with a rifle and six-shooter, complete his happiness. Of vice, in the ordinary sense, he knows nothing. He is a rough, uncouth, brave, and generous creature, who never lies or cheats. It is a mistake to imagine that they are a dangerous set. Anyone is as safe with them as with any people in the world, unless he steals a horse or is hunting for a fight. In their eyes, death is a mild punishment for horse stealing. Indeed, it is the very highest crime known to the unwritten law of the ranch. Their life, habits, education, and necessities have a tendency to breed this feeling in them. But with all this disregard of human life, there are less murderers and cutthroats graduated from the cowboy than from among the better class of the east, who come out here for venture or gain. They delight in appearing rougher than they are. To a tenderfoot, as they call an eastern man, they love to tell blood curdling stories, and impress him with the dangers of the frontier. But no man need get into a quarrel with them unless he seeks it, or get harmed unless he seeks some crime. They often own an interest in the herd they are watching, and very frequently become owners of ranches. The slang of the range they always us to perfection, and in season or out of season. Unless you wish to insult him, never offer a cowboy pay for any little kindness he has done you or for a share of his rude meal. If the changes that are coming to stock raising should take the cowboy from the ranch, its most interesting features will be gone.”

Theodore Roosevelt gave an address, once, up in South Dakota, which is readable in connection with the subject in hand. “My friends seem to think,” said Roosevelt, “that I can talk only on two subjects-the bear and the cowboy-and the one I am to handle this evening is the more formidable of the two. After all, the cowboys are not the ruffians and desperadoes that the nickel library prints them. Of course, in the frontier towns

-282-

where the only recognized amusements are vices, there is more or less of riot and disorder. But take the cowboy on his native heath, on the round-up, and you will find in him the virtues of courage, endurance, good fellowship, and generosity. He is not sympathetic. The cowboy divides all humanity into two classes, the sheep and the goats, those who can ride bucking horses and those who can’t; and I must say he doesn’t care much for the goats.

“I suppose I should be ashamed to say that I take the western view of the Indian. I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indian is the dead Indian, but I believe nine out of every ten are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth. The most vicious cowboy has more moral principle than the average Indian. Take three hundred low families of New York and New Jersey, support them, for fifty years, in vicious idleness, and you will have some idea of what the Indians are. Reckless, revengeful, fiendishly cruel, they rob and murder, not the ‘cowboys who can take care of themselves, but the defenseless, lone settlers of the plains. As for the soldiers, an Indian chief once asked Sheridan for a cannon. ‘What! do you want to kill my soldiers with it?’ asked the general. ‘No,’ replied the chief, ‘Want to kill cowboy; kill soldier with a club.’

“Ranch life is ephemeral. Fences are spreading. all over the western country, and, by the end of the century, most of it will be under cultivation. I, for one, shall be sorry to see it go; for when the cowboy disappears, one of the best and healthiest phases of western life will disappear with him.”

Probably every business has its disadvantages, and one of the great pests of the cattleman and cowboy was the loco weed. This insidious weed, which baffled the skill of the amateur, was a menace to the cattle and horse industry. The plant was an early riser in the

-283-

spring season, and this early bloom was nipped as a sweet morsel by the stock. Once infected by the weed, stock never recovered. The government chemist never satisfactorily traced the origin of the supposed poison of the weed. Stock allowed to run at large on this weed, without other feed, became affected by a disease resembling’ palsy. Once stock acquired a taste for the weed, they could not be kept from it, and never recovered, but, by degrees, died a slow death.

Like its disadvantages, every business probably has its own peculiar words and phrases, and in this the cattle business was not deficient. For instance, the word, “maverick”, is very extensively used among stock men all over the country, and more particularly in localities where there is free or open range. I am told the word originated in this way. A gentleman, in very early times, soon after Texas gained her independence, moved into Texas from one of our southern states, with a large herd of cattle and horses, all unbranded. He was astonished to see everyone’s stock branded and ear-marked, which was not the custom in the country he came from; so he asked his neighbors if they all branded. Oh, yes, they all branded without an exception. So he said, “If everyone brands but myself, I will just let mine go, as I think it is a cruel practice, anyway, and you all will know my stock by its not being branded.” His neighbors thought that was a good idea, but it did not work well for Mr. Maverick, as he had no cattle, to speak of, after a few years; certainly, he had no increase.

The “dead line” was a term much heard among stockmen in the vicinity of Dodge City. As has been stated, the term had two meanings, but when used in connection with the cattle trade it was an imaginary line running north, a mile east of Dodge City, designating the bounds of the cattle trail. Settlers were always on the alert to prevent the removal or extension of these prescribed

-284-

limits of driving cattle, on account of danger of the Texas cattle fever. An effort being made to extend the line beyond Hodgeman county, was promptly opposed by the citizens of that county, in a petition to the Kansas legislature.

The long-horned, long-legged Texas cow has been dubbed the “Mother of the West”. A writer sings the song of the cow and styles her, “the queen”, and, in the “Song of the Grass”, this may be heard above the din that “cotton is king”. A well-known Kansan has said that grass is the forgiveness of nature, and, truly, the grass and the cow are main food supplies. When the world has absorbed itself in the production of the necessaries of food and clothing, it must return to the grass and the cow to replenish the stock exhausted in by-products. At Dodge City now, however, the open range and the cattle drive have been supplanted by the wheat field and the grain elevator. In the early times, cattlemen and grangers made a serious struggle to occupy the lands.

But destiny, if so it may be called, favored the so-termed farmer, “through many difficulties to the stars.” The time and the occasion always affords the genius in prose and rhyme. The literary merit is not considered, so that the “take-off” enlivens the humor of the situation; so here is “The Granger’s Conquest”, in humorous vein, by an anonymous writer:

“Up from the South, comes every day,

Bringing to stockmen fresh dismay,

The terrible rumble and grumble and roar,

Telling the battle is on once more,

And the granger but twenty miles away.

“And wider, still, these billows of war

Thunder along the horizon’s bar;

And louder, still, to our ears hath rolled

The roar of the settler, uncontrolled,

-285-

Making the blood of the stockmen cold,

As he thinks of the stake in this awful fray,

And the granger but fifteen miles away.

“And there’s a trail from fair Dodge town,

A good, broad highway, leading down;

And there, in the flash of the morning light,

Goes the roar of the granger, black and white

As on to the Mecca they take their flight.

As if they feel their terrible need,

They push their mule to his utmost speed;

And the long-horn bawls, by night and day,

With the granger only five miles away.

“And the next will come the groups

Of grangers, like an army of troops;

What is done? what to do? a glance tells both,

And into the saddle, with scowl and oath;

And we stumble o’er plows and harrows and hoes,

As the roar of the granger still louder grows,

And closer draws, by night and by day,

With his cabin a quarter-section away.

“And, when under the Kansas sky

We strike a year or two that is dry,

The granger, who thinks he’s awful fly,

Away to the kin of his wife will hie;

And then, again, o’er Kansas plains,

Uncontrolled, our cattle will range,

As we laugh at the granger who came to stay,

But is now a thousand miles away.”

-286-