(from Reminiscences of a Soldier’s Wife, by Ellen McGowan Biddle, 1907)

[During 1873, Captain James Biddle, his wife Ellen, and their two young sons Dave and Jack traveled from Fort Riley, Kansas to Fort Lyon, Colorado (about 5 miles from Las Animas), where Biddle was to assume command of the post. Of particular interest is Mrs. Biddle’s description of the Dodge House in Dodge City. Captain James Biddle was always called “Colonel” from having held that brevet rank during the Civil War. Captain Biddle later became the commander of Fort Grant, Arizona Territory and there played a minor role in Wyatt S. Earp’s vengeance ride in 1882.]

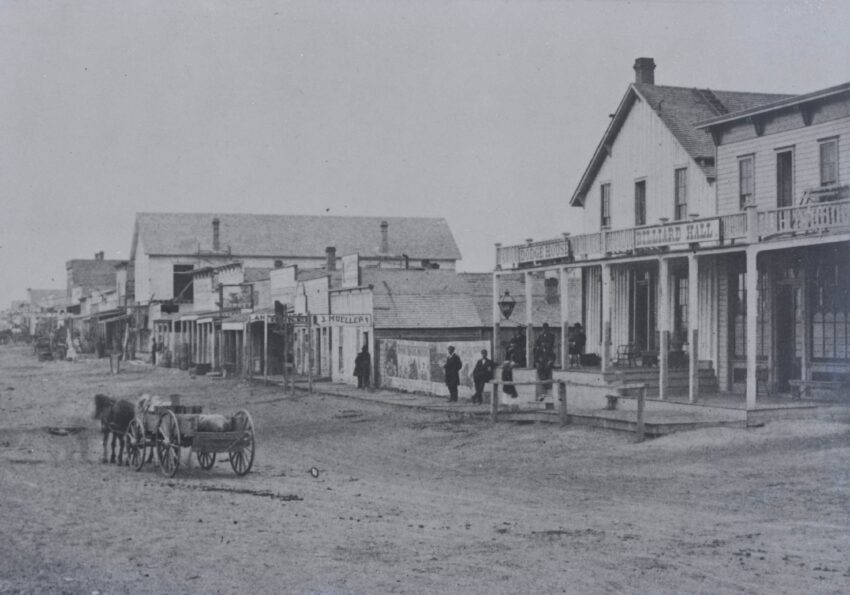

The journey to Fort Lyon was full of interest. We went by the Atchison and Topeka Railway, which was then new. There had been heavy rains and floods, and we travelled slowly, seeing countless antelopes and buffaloes. The train actually stopped while some English and American tourists shot a few of them; it was most exciting. Dodge City was then the terminus of the road, a terrible little frontier town. On arriving we went to the hotel to remain over night. It was a wooden building, without paint or wash of any kind, with two front doors, one leading into a saloon, the other into a parlor. There was a yellowish green ingrain carpet on the floor, a “suit” of furniture covered with majenta [sic] plush with yellow figures in it, coarse Nottingham lace curtains at the windows and some vivid chromos on the walls.

The children, maids and I entered this room, while the Colonel went in search of the host. He soon returned and with him a woman with a hard face, fully six feet tall and of very large frame. She was dressed in a “bloomer” costume–full blue trousers drawn in at the ankle, and a long blue sacque reaching nearly to the knee; a knife and pistol were in her belt. While she talked to me Dave got up in the middle of the room and, pointing at her, laughed aloud and said: “Look at her, Jack; isn’t she funny? Look at the knife, Jack.” I was terrified lest she would kill him, but she quietly turned to him and said: “Come with me and get some cake and milk.” I was afraid to let him go, but his father had nodded consent, and away he went. Poor Jack, who had not laughed at her audibly, was not invited.

After supper, which was not bad (but the first time I had eaten buffalo meat), we went to our rooms, in the second story of the house, reached by narrow open steps. There was one big room divided two-thirds of the way up into smaller rooms by white heavy muslin stretched across, all open at the top. There was a wooden bedstead, chair and small table with pitcher and basin on it in each room; the latter was about 6 x 10 feet. The children, maids and I went to bed, for we were tired; the Colonel came later, as there were many soldiers around and he wanted to keep his eye on the man who was to drive us the next day to Fort Lyon.

Fort Dodge was about five miles distant, and the soldiers on pass came to the town, drank villanous [sic] whiskey which these saloons kept, and after a drink or two the men would be crazy drunk, their clothes and everything they had with them stolen, and when the saloon-keepers had gotten all they possessed they were thrown out into the streets. This was before the days of the canteen, which remedied everything for the time; but the liquor dealers were too strong for the law-makers, and the canteen, where no whiskey was sold, had to go, so the conditions are about the same as before; there is always a grog-shop on the outskirts of every garrison.

About midnight we were all awakened by pistol shots. The Colonel was in his clothes and downstairs in a minute. There was a genuine fight on hand, pistols and knives being used. The floor of our rooms and the ceiling of the saloon was but one board thick, so we heard it all and feared some of the shots might reach us. The Colonel returned after a time, when all was quiet, but there was not much sleep to be had, and I was heartily glad to have an early breakfast and shake the dust of Dodge City from my feet. I am told it is now a flourishing city.

We had a comfortable ambulance, four mules, and a good driver. The Colonel sat in front with the driver, to be on the lookout; we had no escort, excepting the few men on the baggage-waggons; [sic] the Indians just at this time were considered peaceful. The ride was most interesting. We saw great herds of buffaloes, antelopes, and much small game, which the Colonel occasionally shot for our meals. Once when we were about to ford the stream we waited for some buffaloes to cross, but when our driver found it was an unusually large herd and our mules very restive we drove a mile or two along the bank and made a crossing. We could see across these plains for many, many miles, owing to the condition of the atmosphere.

The country was entirely different from the sage-brush plains of Nevada, and the mountains were far in the distance, but nothing can be more monotonous and drear than the aspect of these prairies; nothing meets the eye but the expanse of arid waste, not a tree or shrub to be seen except on the little streams where the cottonwood grows. Shortly before arriving at the post, a young cavalry officer rode up and, dismounting, introduced himself to the Colonel (who had gotten down from the ambulance) as Lieutenant George S. Anderson, Sixth Cavalry. Although he had never before met us, he had ridden out about fifteen miles to welcome us to Fort Lyon, and to offer us the use of his quarters until we could get ours in order. It pleases me to think that this friendship begun that day, on the desolate Western prairie, has never been broken.