[Excerpt from Dodge City and Ford County, Kansas 1870-1920 Pioneer Histories and Stories. Copyright Ford County Historical Society, Inc. All Rights reserved.]

Harvey Houses, don’t you savvy;

clean across the old Mojave,

On the Santa Fe they’ve strung ’em

like a string of Indian beads

We all couldn’t eat without ’em but

the slickest thing about ’em

Is the Harvey skirts that

hustle up the feeds

-J.C. Davis

Dodge City has an intimate history with the railroad. After all, it was the railroad arriving here in 1872 on its way to Colorado, that enabled Dodge City to really get going, shipping first buffalo hides and bones and then the cattle and meat that brought the cowboys that made Dodge City history, these rails running right along with the tracks of the Santa Fe Trail that had brought so many travelers west. The success of the railroads here was intertwined with the entrepreneurial skills of an English immigrant, Fred Harvey, who began a chain of eating places called Harvey Houses that both civilized and popularized railroad travel.

And even though the railroad no longer plays a prominent part here, Dodge Citians are still proud of the beautiful Santa Fe terminal that replaced, in 1898, the simple boxcar building first used as a depot and a later frame building. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad showed its faith in Dodge City’s future and that of their railroad to attract tourist traffic as well as regular passengers by investing $50,000 to build this new depot and landscape the grounds around it, including two huge sundials to alert travelers to the changing time zones from standard to mountain. These sundials still do their job today.

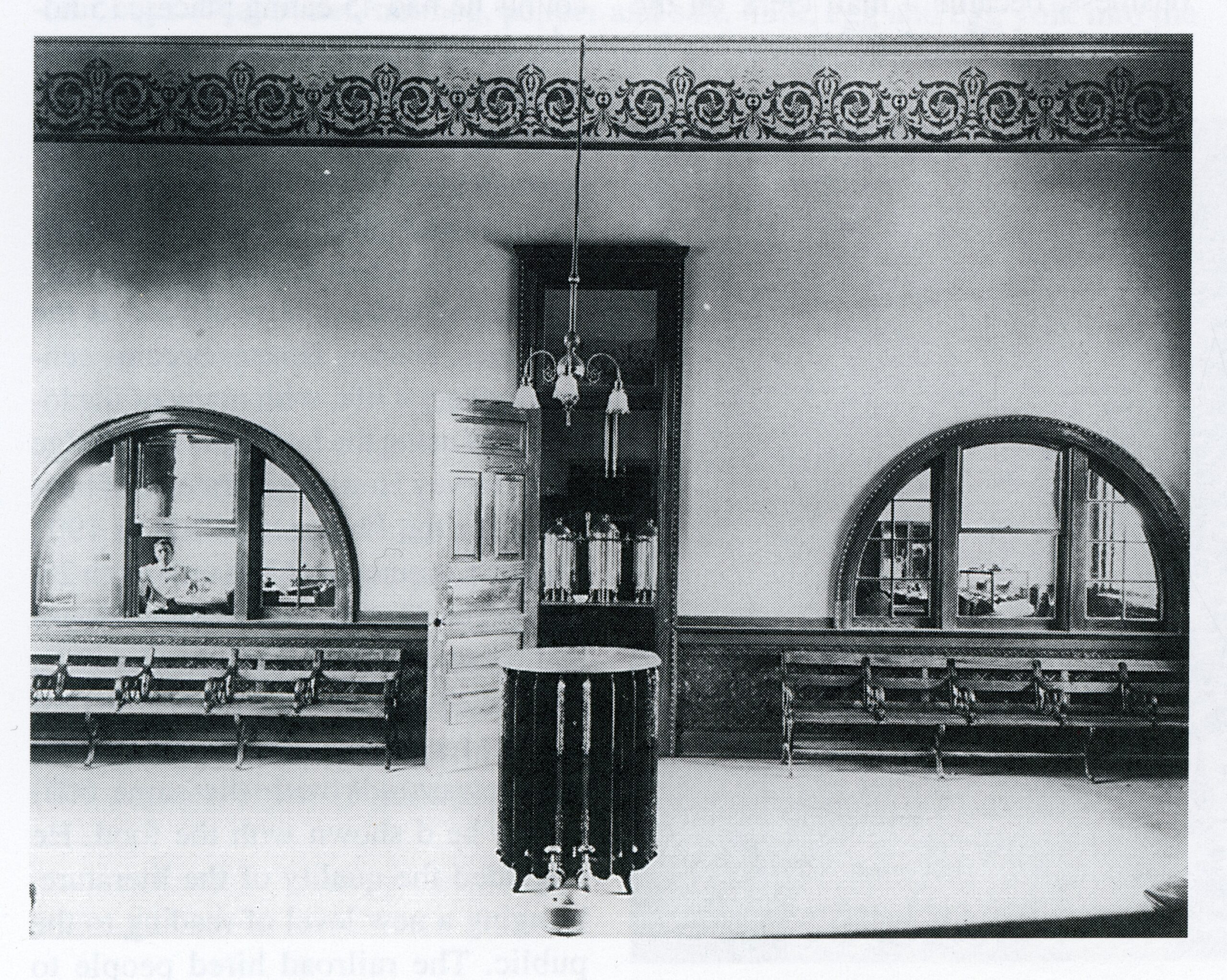

According to the April 8, 1897, Globe-Republican, newspaper of the day, the building was to be of “brick and stone with stone concrete foundation, tile roof, corrugated iron mansard, and windows of plate glass. The main building will be 255 feet by 58.4 feet. On the first floor will be the waiting rooms, baggage and express offices, ticket office, lunch counter, hotel office, dining room, sample rooms, kitchen, bakery, store room, refrigerators and all the necessary appurtenances of a well-equipped hostelry. The second story is 175 x 42 feet and is divided into commodious chambers and bedrooms. The building will be one of the finest on the line of the Santa Fe road, and it is to be surrounded by a magnificent and beautiful park.”

And on October 14, 1897: “The new depot and eating house building is constructed with a view of being fireproof. Iron awnings have been put up and are covered with sheet iron. The balconies are covered with copper and sheet iron and copper lining is placed on exposed woodwork. Terra cotta, or tile, covers the roof and the hips with copper. The kitchen floor and where fires are used, is laid in cement and brick. One coat of cement plastering has been put on. The building will have ample sewerage, the pipe having been laid as far as the river. As the building nears completion, its grandeur is apparent. It will certainly be an architectural beauty and the best building of its kind on the lines of the Santa Fe Railway.”

And the restaurant inside was just as beautiful, as the Dodge City Daily Globe of 1914 indicates “…a large dining room where 108 guests may be served at one time. The dining room is silver gray with black inlay, and the light cool grays and blues in which the paneled wainscot, the walls and woodwork are finished – more inviting surrounding for a dining room are difficult to imagine.” By 1941, there were “…polished hardwood floors, hand-decorated window shades by a Kansas City artist, wood paneled walls, French silver coffee service, low soft lights on each table beside the wall.”

In February 1898, a big gala was held to dedicate this great achievement of the new depot. Tickets went on sale at P.H. Young’s Jewelry Store for a dance at McCarty’s rink with music from Beeson’s orchestra. A meal for 200 was served at 11 p.m. in the new dining room with flower-bedecked tables, the Honorable. E.H. Madison serving as toastmaster. It was 3 a.m. before everyone went home that night.

Inside this new brick Prairie-style building with Harvey House and Hotel to serve railroad passengers and townsfolk alike were the Harvey Girls, winsome misses with long black dresses eight inches from the floor, black stockings and shoes, and stiffly-starched, immaculately clean white aprons and white “Elsie” collars, their hair in a net tied with a white ribbon and no makeup.

They came from all parts of the country and even around the world, from back east and some major metropolises, but as many as half of these girls came from the Great Plains areas where their families had settled for farming and other pursuits.

Imagine being a young girl then, and answering the following ads, which first appeared around 1883, in newspapers and magazines back east and in the Midwest:

WANTED: Young women, 18 to 30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent.

After being disgusted with men who had previously worked as waiters and managed to get themselves cut up, shot, etc. (in Raton, New Mexico, specifically) Fred Harvey and associates hatched the idea to hire young women who would be less likely to get into brawls and not show up for work. It worked so well in Raton, that he sent the ad onwards nationally. Thousands of girls answered the call for employment and thousands were hired after their backgrounds were thoroughly checked out for suitability. Usually, they had around 24 hours to get packed and started for their destination, an intensive training program at some Harvey House, often located in Kansas, and then rail passage to their first Harvey House as a Harvey Girl!

Here in Dodge City, as at each Harvey House, they started out with a base wage of $17.50 a month plus room and board, living in a dormitory with strict rules. They entered into the Harvey extended family where they were well cared for. Their curfew was 10 o’clock, their dating strictly supervised, they had to be scrupulously clean, and even their jewelry and hairstyles were closely monitored, thus ensuring their families of their continued safety and sanctity on the wild plains. Perks of the job were delicious meals for themselves, tips from the customers, and free rail passage. They could take trips all over and hike and sight-see through the country. The girls could also go home during harvest or other busy seasons on their family farms and return to their jobs when the seasonal chore was done. Schoolteachers made excellent summer replacements until the girls returned.

They learned to do amazing things, serving meals quickly and efficiently to as many as 100 passengers arriving from two to three times a day.

In fact, Johanna Klenke, daughter of Henry Klenke of Bellefont, Kansas, herself a Harvey Girl along with sisters, Katie, Mary, and Josephine, stated, “At the time, I don’t think Harvey Girls were aware of how professional they were.”

When the passengers arrived hot and dusty, tired and bored, they entered another world inside the Harvey House: elegance and luxury were the order of the day, Irish linens, English silver, stenciled walls, walnut furnishings, fabulous menus, well-groomed help, and most importantly, fantastically edible food, a far cry from the horrors most of them had been subjected to before Fred Harvey perfected his system. Top-notch chefs, sometimes even European chefs, were lured with large salaries.

Everything was organized so that diners were even served their drinks immediately upon sitting down. The same menu was never offered twice to the same passenger all along the line. The menus were printed in Kansas City and sent by Harvey to all his establishments so that he was able to keep a wide variety of choices set before the guests. While dining, customers were never hurried by the train people, a far cry from the past, though the establishment itself would be a beehive of activity to pull off this feat. Perhaps a series of train whistles alerted the stations ahead of the orders of the customers or maybe the telegraph did the trick! Drink orders were taken, and then cups adjusted so that the drink girl could quickly tell what to give the customer:

Cup upright in the saucer meant coffee. Cup upside down in the saucer meant hot tea. Cup upside down, tilted against the saucer meant iced tea. Cup upside down, away from the saucer meant milk. Only if the customer fiddled with his cup, would the order be wrong!

Harvey achieved all this by demanding excellence and generosity from his employees, preferring to operate at a loss rather than cut corners or slice meat a little thinner. Pies were traditionally cut into four pieces rather than today’s six. He had a contract with Santa Fe that allowed him exclusive rights to the eateries, and free ice, water, and coal to be transported wherever he needed it. He could furnish uniform water that was shipped in if the local water wasn’t good, make uniform coffee blends with good water so that all the coffee tasted alike, provide fresh meat and game by buying from local producers such items as terrapin, antelope, quail, blue point oysters, (later safe food laws prevented some of this), purchase fresh vegetables and fruits, and by the time the railroad reached California, he shipped fancy Kansas City fillets of beef, a Harvey House Specialty, all along the lines and fancy fruits from California and places west. He had his own dairies along the way, including one in Newton, Kansas. Later he had his own ranch, the XY Ranch near Lakin, Kansas. So he had the means to keep food uniform and of top quality all along the 12,000 miles of Santa Fe track.

He held legendary surprise inspections all along the line, arriving with white handkerchief to check out the establishment better than, if not equal to, any army inspection! Managers found cutting corners pouring orange juice out of a jug kept in the refrigerator rather than squeezed fresh as needed, chipped plates, waitresses, cooks, any one with signs of less-than-perfection, prompted harsh rebukes and perhaps outright firing on the spot, with quick replacement by trained employees from his other establishments. Working at one Harvey location meant you could work at any Harvey location, fitting in quickly and expertly. Meals started out at five cents and by the 1880s, were 75 cents and as much as $1.75 by 1928.

Who was Fred Harvey? He came to America in 1850, from England when he was only 15 years old. He first worked in an eating establishment in New York, probably developing the ideas of how food should be served, then made his way to St. Louis, where he operated a restaurant. He married Barbara Sarah “Sally” Mattas and eventually, after the Civil War disrupted his business, became a mail clerk on the railroad, deciding that this was his future as he traveled along the rail lines on business. He became a freight agent and was promoted to general western agent. He was sent to Leavenworth, Kansas, from where he ran his offices for years until moving them to Newton. He saw a need for better quality and better-served food on the railroads and decided to collaborate on a business venture with the Santa Fe Railroad.

Santa Fe officials had just had a disastrous experience on an official excursion to Pueblo, Colorado, in March 1876, after the railroad had just reached that city. The train was caught in a blizzard and the passengers were forced to eat (or not eat what wasn’t edible) the common railroad food of the times. Harvey approached them with his ideas of proper food management at a very opportune time! His first Harvey House opened in Florence, and it was such a success that subsequent eateries were opened approximately every 100 miles along the tracks. In 1900, the railroad travel brochures were claiming “the dining service under the management of Fred Harvey is the best in the world.”

Harvey’s final contract with the railroad was signed December 6, 1899. On February 9, 1901, he died at the age of 65, with intestinal cancer. By some accounts he had 45 eating places, 15 hotels, and 30 dining cars, in 12 states at the time of his death. His heirs kept his empire going until 1968 doing as well as he did at keeping quality control.

Since small towns along the rails all through the Great Plains now had access to the same quality of food as the big cities, Harvey Houses became centers for social life, with many of the local clubs using the facilities. The Dodge City Harvey House was the site of banquets for the Philomath Club in 1901 and the Commercial Club on March 28, The Dodge City Harvey House had a reading room and the Santa Fe contracted with Harvey in 1897 to provide the reading literature and magazine and newsstands with the same efficiency he’d shown with the food. He upgraded the quality of the literature, bringing a new level of reading to the public. The railroad hired people to present Chautauquas along the lines for their Santa Fe employees starved for more culture. One such was Queen Stout from Iowa, hired as an elocutionist around the age of 20. She presented her first Chautauqua in Dodge City, in February 1911, moving her audience to tears as she recited Captain January.

And then there were the Harvey Girls themselves, immortalized forever in The Harvey Girls, an MGM movie starring Judy Garland that came out in 1946. These girls brought dignified manners, a taste for attending church and community events, and in general, a little class to the unruly, wild West, charming many of the local cowboys, ranchers, railroad officials and town dignitaries right into marriage. It is estimated at least 5,000 girls did marry, and many eventually filled important spots in their communities as leaders of the day. These Harvey Girls had a tremendous impact by filling a spot sorely needed in a rough and tumble atmosphere where many men had never seen the likes of them before.

Fred Harvey was greatly respected. So much so, that many Harvey Girls named their boy babies Fred or Harvey, in the years to come, even sometimes after they had quit working as a Harvey Girl to be married. If they quit before their contracts were up, they had to forfeit their pay. It was said that Fred Harvey personally congratulated any girl who made it to the end of her contract without marrying. These contracts usually started out being for a year, but were gradually changed to a length of six months, since a year was oftentimes hard to meet if romance was in the air! Even after his death, Fred Harvey exerted tremendous influence on his employees. He was a much beloved man.

In August 1914, a Santa Fe Superintendent, T.C. Dice, selected a new name for Dodge City’s Harvey House. He chose El Vaquero, which is Spanish meaning The Cowboy. This was considered appropriate for the city’s image. Much of the cattle drive terminology was taken from Spanish since the cattle were driven up from Texas where Spanish was spoken.

By 1936, girls in Dodge City, were earning $25 a month plus tips and free room and board, according to Viola Crebs, quoted in The Hutchinson Herald on March 18, 1971. Also, the curfew was moved to 11 p.m. when the doors would be locked. Duplicate keys were sometimes used to sneak out, so the management would change the locks occasionally. By this time, the girls could wear white blouses and black skirts that covered the knees. Hairnets were still required, and rings and watches could be worn, but earrings, combs or any other jewelry was prohibited. From 200 to 300 guests crowded off the trains to be served by 28 girls in the lunch room and 20 Harvey Girls in the dining room.

According to Viola Crebs, the Dodge City Harvey House was such a large, swanky place that it attracted the big movie stars traveling to and from each coast. She states that she had the opportunity to serve or meet Greta Garbo, Cary Grant and Mae West. Other famous people were also here at times. Vice-President Roosevelt ate breakfast here as reported on August 16, 1901.

Fred Harvey himself had ties to Dodge City. His wife, Sarah, was a sister to Margaret Hardesty, wife of the cattle baron whose home graces Boot Hill as a museum. Because of this family connection, he visited here often during the early railroad days.

Boot Hill Museum set up an exhibit in 1990, which shows a reproduction of the stencil design used at Dodge City’s Harvey House. Also on display are photographs, silver tableware, menus, playing cards, various table settings and a cash register that was used in the restaurant.

With the decline of the railroad because of automobiles and airplane travel and trucks as primary carriers, and with increasing government regulations, the Harvey conglomerate eventually ground to a halt, though dining cars were tried for awhile and Harvey did serve some excellent air meals. But for various reasons, in 1968, the partnership with the Santa Fe Railroad was dissolved and an era came to a close. The Dodge City El Vaquero itself closed in 1948. At this closing, a special party was served – eight persons were there who had attended the original dedication back in 1898: Dr. and Mrs. C.W. McCarty, Merritt Beeson, C.N. States, F.A Hobble, Mrs. O.H. Simpson, John B. Martin and Judge Karl Miller, who was only a little boy at the time and told of peeking through the windows to watch the others eat!

A large part of the grand depot itself has lain idle since 1957, when the last hotel rooms and the newsstand were closed. However, in the near future, the Boot Hill Repertory Theater plans to remodel and reuse the facilities of the old Harvey House for its dinner theaters. This will be a wonderful use for the graceful old building, salvaging this grand landmark as a truly important piece of Dodge City’s history.

Ann Warner

Adapted from Dodge City Daily Globe, The Globe-Republican, The Hutchinson News Herald,

The Harvey Girls and Meals by Fred Harvey

Dodge City and Ford County, Kansas 1870-1920 Pioneer Histories and Stories is available for purchase from the Ford County Historical Society.