[Excerpt from Dodge City and Ford County, Kansas 1870-1920 Pioneer Histories and Stories. Copyright Ford County Historical Society, Inc. All Rights reserved.]

Rural schools were of prime importance in Ford County. In 1877, Baldwin was the first rural district to be organized. District #62, the Riney school in 1926, was the first rural district to elect to send its students to the Dodge City schools instead of maintaining its own school. Between 1877 and 1926, more than 50 school districts had been established. Several of these districts had more than one school. In fact, Grandview, a district north of Wright, maintained five schools. During 1887 and 1888, the years of the greatest settlement in the county, 40 school buildings were erected.

Each district was administered by a three-member school board which was elected at an annual meeting. This board was, in turn, responsible to the county superintendent. Each district hired its teacher, set the salary and named the various added duties which included carrying the drinking water and coal to the school, sweeping, cleaning and other janitorial chores. The teacher also acted as nurse in emergencies, counselor, entertainment director, nutritionist and proxy parent.

No one disputes the importance the rural school and its teacher played in the culture at that time. Students and their parents were fiercely loyal to their school which educated children from the first through the eighth grade. The one-room building, heated by a coal or wood stove, lighted on cloudy days with kerosene lamps, was not only the schoolhouse but the community center. It was the meeting place for literary clubs, Sunday School, pie suppers, neighborhood socials and other entertainment. Without a doubt, the district school was one of the sustaining influences in pioneer days.

Betty Braddock

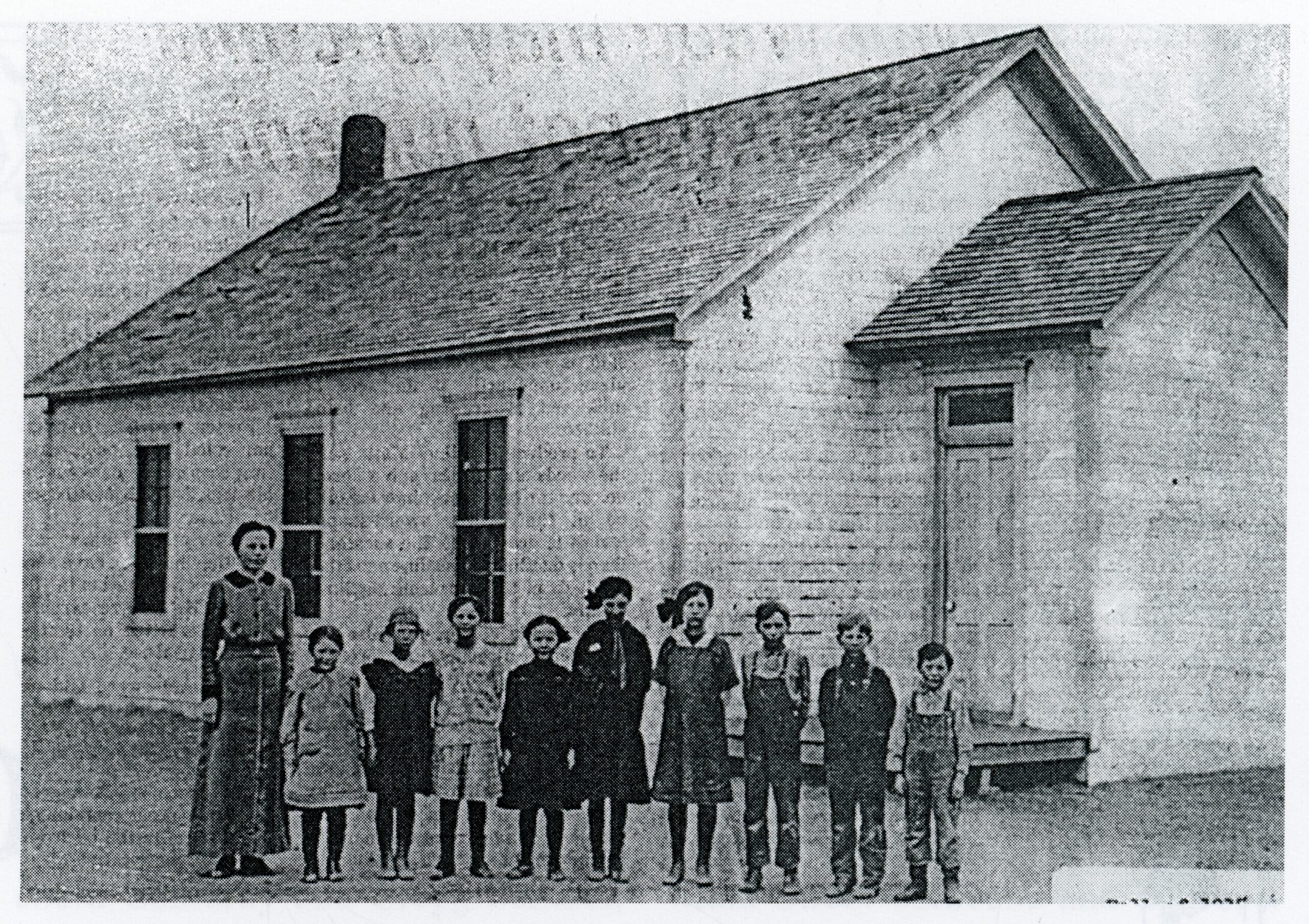

LITTLE WHITE SCHOOL HOUSE

The little white country school house, like the buffalo and the horse and buggy is fading into a dim historical memory. There was a time when it was the center of the community and the haven of learning. Nearly all of the school houses were made of lumber, but and the lessons of life that made them there were a few made of brick. Two small narrow buildings stood several yards back of the school house, one door marked, “boys,” and the other door, “girls.” A big black pot-bellied stove was in the center of the school room where all could gather close on a cold day. A row of desks or benches were on both sides of the stove. The teacher’s desk was up in front on a little platform with a blackboard behind it. Just inside the front door was a small anteroom where the coats, caps and sunbonnets were hung on large substantial nails. On days when heavy overshoes were worn, they were put on the floor beneath the coats. On the other wall was a shelf for lunches, which were brought in shiny molasses buckets or lard pails. There were different sizes and shapes but ventilation was the same in all: nail holes in the top. Inside the dinner buckets were to be found bologna and jelly sandwiches, hard-boiled eggs, a cup of navy beans and possibly an apple. Also in the anteroom was the water pail, but with the long-handled dipper. Everyone drank from the same dipper, no one knew anything about germs, so why worry.

Our forefathers learned the three R’s and the lessons of life that made them the leaders of America. Standard equipment for most classrooms included McGuffey’s Reader, a physiology chart near the teacher’s desk, a few maps on the wall and a globe to show that the world was round.

Pupils were kept in line by the hickory stick or thoughts of it, but this didn’t keep them from now and then shooting paper wads at the ceiling. Making a paper wad was an art; a scrap of paper was chewed until it became a pulpy mass and then propelled to the ceiling by the thumb. If it were done right, it stuck there and dried. In time the wad was covered with fly specks and dust, becoming a permanent part of the decorations.

The curriculum was simple: reading, writing and arithmetic and the old standbys, history and geography. A fancy subject like science was unknown. There was no library, and a school with a big fat Webster’s Dictionary was considered very lucky. Every pupil had a slate, as paper tablets were expensive and were used only on special occasions, such as an essay to be written at home.

The teacher boarded at a farmhouse. She tried to get a place within a mile or so of the school house, so the walk would not be so far. In the early days, a teacher was hired for 20 to 25 dollars a month and they would pay seven to nine dollars for board and room. The teachers and pupils walked to school through wind, rain and snow. Lucky and exceptional was the person who had a horse or mule to ride to school. In winter, darkness came before the farm home was reached, if the distance from school was far. Education in those days came the hard way, but the pupils seemed to turn out all right in spite of, or perhaps because of, their country school education.

The mid-morning and mid-afternoon recesses, and noon hours were the high spots of the day. The games were Fox and Geese, Three-Corner Cat, Ante Over, Crack the Whip, Black Man, Baseball, Dare Base and Leap Frog. On Friday afternoon, the teacher would often have a spelling or a ciphering match, which was a welcome event. Sometimes the school enrollment would not permit choosing sides as there would not be enough to do so. Many schools had 12 or less. The writer of this article was the only pupil in her school for long periods of time. The teacher boarded at her parents’ home and the school board was made up of her parents and a railroad section hand. Sometimes when there was a little disagreement between the teacher and the pupil, the school board seem to lean toward the pupil. A country teacher would teach all eight grades in more populated areas.

Once during each term of school, the county superintendent came to visit. The pupils were supposed to act their best, but they were like scared rabbits, as it was also embarrassing to recite before an outsider. The terms of school were short, usually three to six months. This allowed the older children to help work on the farm in spring and early fall.

Times change, the years pass, but for those who attended the country school, the memories do not fade.

Mrs. Annie E. Scott

Used by permission of Sam Scott, Myrland Scott Hertlein, Wilbur Scott and Josephine Swenson.

Dodge City and Ford County, Kansas 1870-1920 Pioneer Histories and Stories is available for purchase from the Ford County Historical Society.